Dr. Amelia Hartmann1, Prof. Daniel Ruiz2*

1 Department of Political Science, University of Cambridge, UK.

2 School of Global Affairs, New York University, USA

* Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. John Rhodes, Department of Political Science University of Cambridge, CB2 1TN, United Kingdom Email: [email protected]

Abstract

The spread of information pollution presents a profound threat to democratic governance by eroding citizens’ ability to make informed choices and weakening societal trust. The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in the creation of deepfakes, amplifies these risks by blurring the distinction between authentic and manipulated content, thereby shaping public opinion in deceptive ways. Marginalized groups are disproportionately exposed to such harms, often resulting in both online harassment and real-world violence. Although numerous policy tools exist to address information pollution, discourse in this field remains largely restricted to content regulation. Several international initiatives have recently been introduced to protect information integrity, especially during electoral processes. However, diverging national strategies on data governance and the global drift toward authoritarianism hinder consensus on a unified international stance. Moreover, cooperation between governments, civil society, and technology companies remains limited. Strengthened engagement with private sector actors will be essential to building an effective global governance framework. The Global Digital Compact, to be debated at the upcoming UN Summit for the Future (22–23 September), is a key step toward establishing principles for collective digital security.

This policy paper reviews international responses and evaluates existing instruments to mitigate information pollution. Key recommendations include:

- Advancing multilateral and cross-sectoral partnerships to develop a global regulatory architecture for a secure, inclusive digital environment.

- Shifting emphasis from politically contentious content moderation toward content-neutral strategies, including the integration of AI to enhance scalability.

- Designing context-sensitive interventions, ensuring that tools are adapted to local circumstances and informed by rigorous evidence before integration into policy frameworks.

- Pursuing long-term, systemic approaches that strengthen resilience, support independent journalism, promote free information flows, and embed information literacy within education systems.

Keywords:

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

1. Introduction

The growing prevalence of information pollution represents a profound challenge to both democratic governance and social stability across the globe. The health of democracy depends on an electorate that has access to reliable knowledge, is able to freely express opinions, and benefits from independent media as well as equitable access to information. When people are equipped with factual, balanced information, they can make responsible decisions in political and economic spheres. Yet, exposure to misleading, conflicting, or distorted narratives on digital platforms has been shown to heighten political polarisation while simultaneously eroding confidence in democratic institutions and the reliability of information as such. These dynamics are particularly pronounced during electoral periods, when manipulative communication strategies are deliberately deployed to delegitimise political rivals, silence critical journalists, or discredit election authorities and democratic processes. Efforts to undermine the integrity of information are not incidental but represent a core tactic of authoritarian governance, where disinformation is purposefully applied to secure or expand political power.

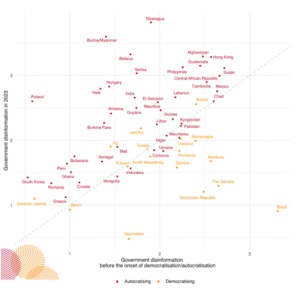

Figure 1 captures this association between disinformation practices and regime change. The vertical axis reflects the extent to which governments spread false or distorted content within their borders, while the horizontal axis displays disinformation levels before the onset of episodes of democratisation or autocratisation, which began at different points across countries. Only states experiencing a regime shift are included, classified as either “democratising” or “autocratising” as of 2023. Although only descriptive, the figure suggests that governments undergoing autocratisation are more likely to engage in high levels of disinformation.

Figure 1: The amount of disinformation disseminated by governments domestically and political regime transformation (autocratisation or democratisation)

Despite the seriousness of this issue, there remains no universally accepted terminology to describe the circulation of manipulated or poor-quality content. Widely used expressions such as “fake news” are overly narrow and have been weaponised by politicians seeking to delegitimise independent media outlets. By contrast, the broader, more neutral concept of “information pollution” (UNDP, 2022) is useful for capturing the spectrum of low-quality material circulating in the information ecosystem. This framework distinguishes between different forms based on intent and mode of dissemination. Misinformation refers to inaccurate or misleading content shared without the deliberate aim of causing harm. Malinformation involves the distortion or weaponisation of genuine information for harmful purposes. Disinformation entails deliberately fabricated content created with malicious intent and spread through mechanisms that extend beyond traditional journalism, including automated bot networks, micro-targeted advertising, coordinated trolling campaigns, and viral memes.

Mexico provides an illustrative example of these dynamics. Data from V-DEM’s Digital Society Project reveals a sharp increase in government-led disinformation during the presidency of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018–2024). His administration frequently engaged in malinformation and outright disinformation, often targeting journalists with the explicit intention of discrediting their professional reputation (Breuer, 2024). These practices have coincided with a measurable decline in Mexico’s democratic quality. According to V-DEM, the country formally entered an autocratisation phase in 2020.

At the same time, rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are intensifying the digital threats facing democracy. As it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish between AI-generated and human-generated text, citizens may find themselves more vulnerable to manipulation (Kreps et al., 2022). AI-driven outputs are often designed to elicit strong emotional reactions, making them both persuasive and highly shareable. Such material spreads quickly across algorithm-driven platforms and mainstream media alike. Although generative AI is still in its early stages (Garimella & Chauchard, 2024), deepfake technologies are expected to become more pervasive tools for disseminating deceptive narratives.

Beyond their impact on political institutions, these developments also amplify social inequalities. Information pollution disproportionately targets and harms vulnerable populations and minorities, who are more exposed to online harassment and abuse. For example, a global survey conducted by UN Women (2022) reported that 38 per cent of women have endured some form of digital violence. Online hate speech rarely remains confined to the virtual realm; instead, it often escalates into physical violence. In many cases, vigilante groups have coordinated attacks against minorities using social media platforms as organisational tools.

Amid these concerns, the international community has become increasingly alarmed about the potential of information pollution to fuel both political polarisation and autocratisation. The issue has gained additional urgency in light of the “Super Election Year 2024,” during which dozens of countries hold national votes. Reflecting these anxieties, the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2024 ranked misinformation and disinformation as the most serious short-term global risk, underscoring the severity and immediacy of the challenge (World Economic Forum, 2024).

2. Challenges For International Collaboration And Development Cooperation

The global community has begun to place greater emphasis on protecting the integrity of the information environment, most visibly through initiatives such as the UN Global Principles for Information Integrity launched in June 2023 (UN, 2023). Growing recognition of the dangers posed by information pollution has led to its emergence as a central theme in both international policy discussions and development cooperation. For example, the OECD has recently revised its framework for media assistance. In-depth consultations involving journalists, academics, and media development organisations concluded that the earlier OECD Principles from 2014 no longer reflected the contemporary challenges of escalating information manipulation, political polarisation, and the worldwide rise of authoritarian regimes. In March 2024, the OECD Development Assistance Committee Network on Governance (OECD DAC-GovNet) formally endorsed the updated Principles for Relevant and Effective Support to Media and the Information Environment (OECD, 2024). These new principles are directed not only at development agencies but also at international policymakers, political actors, media practitioners, private donors, and investors. Their central message is the need for a holistic and strategic approach that addresses the dangers of manipulated information while safeguarding freedom of expression, particularly in light of the transformative influence of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence.

A second prominent initiative is the Media and Digital working group, which forms part of the Team Europe Democracy (TED) Initiative. This body, tasked with advancing pluralistic media and inclusive democracy under the EU Strategic Agenda 2019–2024, brings together EU donor agencies, researchers, journalists, and advocates for media freedom and the right to access information. Ahead of the UN Summit for the Future, the group presented recommendations outlining how EU member states and the European Commission could ensure that the Pact for the Future incorporates binding commitments to information access, independent journalism, and media freedom. While such initiatives are commendable, serious obstacles continue to hinder meaningful global cooperation to confront disinformation. These barriers can be grouped into four major challenges.

2.1 Structural challenge

The growing global shift toward autocratisation represents one of the most significant barriers to collective action. At present, 42 countries are undergoing periods of democratic backsliding, and nearly half the world’s population lives under authoritarian regimes. Since populist and autocratic governments are themselves among the most prolific producers and disseminators of manipulated information, they have little incentive to participate in a principled global agreement against information pollution. This political reality severely limits the scope for inclusive multilateral cooperation.

2.2 Funding challenge

Another barrier relates to the limited financial commitment of international development actors. Official Development Assistance (ODA) dedicated to safeguarding media freedom and promoting the unrestricted flow of information remains extremely low. According to current figures, only 0.3% of OECD ODA is allocated for these purposes, underscoring a major gap between the recognition of the problem and the resources directed toward solving it. Without stronger investment, international initiatives risk remaining symbolic rather than transformative.

2.3 Sectoral silos challenge

A further complication is the persistence of sectoral silos that prevent effective cross-sectoral collaboration. While awareness of information pollution is growing among corporate leaders, systematic engagement with the private sector is still insufficient. This lack of coordination weakens global efforts in several ways. Firstly, companies may unintentionally finance disinformation networks. Automated digital advertising systems often place corporate advertisements on sites spreading manipulated content, meaning businesses unknowingly support disinformation campaigns during high-profile global events (Ahmad et al., 2024). Secondly, digital platforms themselves must be treated as indispensable actors in any multilateral solution. Their participation is vital, as many design-based interventions to curb information pollution depend on their technical capacity and willingness to act. Positive precedents include WhatsApp’s introduction of “forwarded” labels to reduce viral misinformation and YouTube’s adjustments to promote trusted sources in its recommendation system.

2.4 Tunnel-vision challenge

Finally, ongoing debates on how to respond to disinformation frequently suffer from tunnel vision. Policymakers often prioritise content regulation as the primary strategy, driven by growing concern about the threats posed to electoral processes and democratic legitimacy. This has led to mounting calls for rapid-response mechanisms that could deliver quick fixes during crises. Yet such a narrow approach is problematic, as it risks being both overly reactive and short-sighted. Content regulation alone cannot provide sustainable solutions to a problem as complex, multifaceted, and adaptive as information pollution.

3. Toolkit of interventions to counter information pollution

Public pressure for the regulation of harmful online content remains relatively limited and tends to fluctuate depending on the issue at stake. Although content moderation is widely implemented across digital platforms, it raises a number of ethical dilemmas and practical barriers. By design, moderation is reactive, taking place only after harmful or misleading content has already spread. It also depends heavily on the willingness of platforms to mobilise the necessary resources—something that cannot always be assumed. Furthermore, critics frequently denounce moderation as a violation of freedom of speech, framing it as corporate censorship rather than a public good.

Research suggests that exposure to digital hostility or intolerance does not necessarily increase popular demand for the removal of problematic content. Pradel et al. (2024) find that citizens tend to support removal primarily when misinformation includes threats of violence against minority communities. In such cases, public opinion leans toward prioritising the elimination of harmful speech over free expression. In most other contexts, however, support for content takedowns is modest, and permanent account suspensions often lack widespread approval. De-platforming—the practice of removing accounts that repeatedly spread manipulated information—has nevertheless become a frequently used intervention. Following the 6 January 2021 attack on the US Capitol, for instance, Twitter removed a number of accounts involved in promoting conspiracy theories and disinformation (McCabe et al., 2024). This action curbed the spread of harmful narratives and triggered additional departures of users engaged in similar activities. Yet the measure remains politically divisive. Many critics accuse technology companies of arbitrarily policing speech, and surveys reveal that the public generally shows greater support for deleting harmful posts than for suspending accounts altogether (Kozyreva et al., 2023).

Given the limitations of content regulation and de-platforming, it is vital to recognise the breadth of alternative strategies available. Addressing the “tunnel vision” that reduces the debate to regulation alone, Kozyreva et al. (2024) highlight the existence of a diverse toolkit of interventions, each with distinct benefits and shortcomings. These tools vary in scalability, context-dependence, and long-term impact. Table 1 (below) provides a structured overview, but they can be broadly summarised into three categories: debunking and fact-checking, behavioural nudges, and educational or “pre-bunking” interventions.

Table 1: An overview of the toolkit for combatting information pollution

| Tool | Objective | Effectiveness and/or Scalability | Issues |

| Content moderation and de-platforming | Removal of false or misleading content; suspension of accounts | Effective in curbing spread in the short term; depends on platform resource mobilisation | Often perceived as censorship; limited public support; reactive by design |

| Debunking and fact-checking | Provide factual corrections and logical explanations to demonstrate why content is false or misleading | Effective in reducing misinformation circulation in the short term; resource-intensive; topic-specific | Can reduce trust in media and credible sources; effects may diminish over time; reactive rather than proactive |

| Accuracy nudging | Prompt users to consider the accuracy of a post or headline before sharing | Highly scalable with platform cooperation; small but measurable short-term effects | Effects may decline over time; may only work in specific contexts, partisan groups, or issue areas |

| Pre-bunking | Educate users on how misinformation spreads before exposure | Strong preventive effects; pre-emptive; moderately scalable | Requires periodic “booster” interventions; effectiveness varies depending on the medium used |

First, fact-checking and debunking initiatives attempt to correct false claims after they have circulated. They do so by providing verified evidence and rational explanations of why a statement is inaccurate or misleading. Over the past decade, a global ecosystem of professional fact-checkers has emerged, bound by shared ethical codes and methodological standards (EFCSN, 2024). Second, behavioural nudges are subtle design interventions aimed at influencing online sharing behaviour. For example, accuracy prompts ask users whether they believe a headline is true before reposting it. These reminders exploit the fact that people often value accuracy more than partisan loyalty once attention is drawn to the issue. Twitter’s “Community Notes” system, launched in 2021, is a notable illustration of collaborative nudging, enabling users to collectively provide context for potentially misleading tweets. Third, pre-bunking focuses on proactive education, equipping people with the cognitive tools to identify misinformation before they are exposed to it. Google and Jigsaw’s pre-bunking campaign ahead of the European Parliament elections exemplifies this strategy. Gamified interventions like the Bad News Game—in which players assume the role of a misinformation producer—have also reached millions of users and shown promise in building resilience (Iyengar et al., 2023).

Evidence regarding the effectiveness of these approaches is steadily growing. Fact-checking and debunking have demonstrated success in reducing the spread of false narratives, especially during coordinated disinformation campaigns (Unver, 2020). Accuracy prompts can meaningfully shift online behaviour; Pennycook et al. (2021) show that users become significantly more likely to share truthful rather than false headlines after being asked to evaluate their accuracy. Similarly, pre-bunking interventions display strong potential as a form of “psychological inoculation,” shielding individuals against manipulation before it occurs (McPhedran et al., 2023).

Nonetheless, each intervention carries notable limitations. Fact-checking and debunking are reactive and their effects often diminish quickly. Carey et al. (2022) find that fact-checking does not necessarily reduce overall engagement with misinformation, as people may continue to interact with false claims even after corrections appear. Behavioural nudges, while promising, can produce only modest improvements, and their impact may decline over time or differ across partisan groups. Design-related issues further constrain effectiveness: although Community Notes can reduce the sharing of false posts, their influence is weakened by the time lag between publication of a misleading post and the addition of contextual notes (Renault et al., 2024). Moreover, the medium of intervention matters. Bowles et al. (2023) report that a short WhatsApp message prompting users to verify content proved more effective than lengthy podcasts encouraging similar behaviour. Pre-bunking, too, faces challenges: without reinforcement or “booster” sessions, its protective effects may fade (Maertens et al., 2021).

There are also risks of unintended consequences. Some studies suggest that fact-checking can erode trust not only in false claims but also in the credibility of accurate reporting. Hoes et al. (2024) and Altay et al. (2023) warn that fact-checking, though helpful in the short term, may inadvertently deepen scepticism of mainstream media. This outcome aligns with the goals of disinformation campaigns, which often aim less at persuasion and more at creating confusion and mistrust.

Scalability remains another pressing concern. Fact-checking and debunking are highly resource-intensive, requiring topic-specific expertise and extensive institutional capacity. Their reach is therefore limited. Educational interventions like games or training modules are also difficult to scale beyond specific demographics. In contrast, nudging strategies have higher scalability potential. Pretus et al. (2024) propose an innovative model in which social media platforms integrate a “misleading count” feature alongside traditional engagement metrics, allowing users to flag misinformation. Posts with high “misleading” counts could then be deprioritised, reducing circulation. Such scalable, content-neutral designs may offer promising paths forward.

In practice, the effectiveness of any intervention is contingent on context. Policymakers must therefore carefully assess local conditions before institutionalising such measures. A one-size-fits-all solution is unrealistic, and tools that work well in one environment may fail—or even backfire—in another. Moreover, long-term sustainability requires more than isolated digital measures. The integration of digital literacy and media education into school curricula is essential, particularly for disadvantaged youth with limited educational opportunities. Offline engagement is equally critical, given that over half the world’s population still lacks reliable broadband. Community-based dialogues and awareness campaigns can complement online efforts by reaching vulnerable groups who might otherwise be excluded.

Artificial intelligence itself presents both risks and opportunities. While AI-generated content has dramatically increased the sophistication and speed of disinformation, it can also be harnessed to counter harmful narratives. Costello et al. (2024) demonstrate that conversational exchanges with ChatGPT successfully debunked conspiracy theories among believers in a durable and scalable manner. This suggests that AI-powered tools could play a dual role: amplifying the threat while also providing innovative mechanisms for mitigation.

Ultimately, durable strategies must extend beyond piecemeal fixes. Countering information pollution requires embedding resilience-building measures into broader thematic programmes, including health communication, climate policy, electoral integrity, media development, and the prevention of violent extremism. Strengthening public trust in official information channels, supporting independent media, and ensuring equitable access to credible information are vital. Only by combining scalable digital infrastructure with offline engagement, education, and systemic policy integration can societies effectively confront the evolving challenge of information pollution.

4. Conclusion and Recommendation

The problem of information pollution continues to undermine democratic resilience and social cohesion worldwide. It amplifies polarisation, erodes confidence in democratic institutions, and allows authoritarian governments to entrench their dominance. Tackling this challenge requires responses that move beyond narrow and politically divisive approaches centred only on content moderation. Instead, the global debate should embrace the full spectrum of available interventions, tailoring them to specific contexts and embedding them within long-term strategies. Certain approaches—such as accuracy nudges and pre-bunking—have emerged as credible alternatives, yet their effectiveness and scalability vary according to situational factors. For these interventions to be applied meaningfully, cross-sector collaboration is essential, particularly with digital companies and corporate actors who shape the information environment. Without their involvement, efforts to operationalise the intervention toolkit risk being fragmented or limited in reach.

A useful example of corporate engagement is Google’s pre-bunking initiative prior to the European Parliament elections, which combined early-warning strategies with partnerships between civil society organisations and think tanks across Central and Eastern Europe to enhance media literacy and expand research capacity (Green, 2022). Nevertheless, such actions remain exceptions rather than the norm, and international collaboration involving businesses continues to fall short. For meaningful progress, the active participation of technology companies is critical, both in financing and in co-designing interventions. Their inclusion will allow the creation of a sustainable transnational framework to safeguard information integrity.

The upcoming Summit for the Future, scheduled for 22–23 September, provides a strategic opening to build this framework. The draft Global Digital Compact (UN, 2024), released in April after multiple consultation rounds with stakeholders, is expected to be annexed to the Pact for the Future if approved by governments. This Compact sets out new standards for corporate accountability and insists that technology companies integrate human rights principles into emerging technologies, while also addressing AI-related risks. Specifically, the draft provisions call for joint industry accountability frameworks (Art. 29b) and collective measures to secure an open, inclusive, and safe digital environment (Art. 59). Ensuring these provisions remain intact during negotiations is crucial for motivating technology firms to take actions that extend beyond episodic content moderation, helping to build a resilient and trustworthy information space.

On the basis of these findings, four key recommendations are proposed:

- Adopt a diversified toolkit of interventions. Global discussions should expand beyond polarised debates on content moderation. Instead, policy frameworks should prioritise tactics that rely less on constant human moderation and more on scalable, content-neutral solutions that proactively mitigate information pollution in real time.

- Ensure rigorous design and testing of interventions. No single tool can comprehensively address information pollution. Although approaches such as pre-bunking appear promising, their impact is often context-dependent and may diminish without reinforcement. Policymakers must carefully evaluate these tools before embedding them in long-term strategies. Scalability should also remain central, with AI-powered systems leveraged to extend the reach and durability of educational interventions.

- Invest in long-term digital literacy and offline resilience. National governments and international development partners should dedicate funding to enhance citizens’ ability to recognise and resist harmful narratives. This requires integrating offline initiatives—such as media literacy campaigns, school-based programmes, and community dialogue platforms—to reduce vulnerability to disinformation and to counter its consequences in both online and offline settings.

- Develop a binding transnational regulatory framework. Protecting information integrity demands coordinated action across borders, with businesses included as core stakeholders. Because a small number of technology companies control global information flows, it is imperative to establish a system that emphasises transparency, accountability, and independent oversight. Such a framework will only succeed through multilateral and multisectoral collaboration. The forthcoming Global Digital Compact offers an unparalleled opportunity to lay the groundwork for such cooperative governance.

In conclusion, information pollution cannot be addressed through piecemeal or short-term interventions. Sustained efforts must combine technological innovation, civic education, regulatory reform, and corporate accountability within an inclusive international framework. The Summit for the Future represents a crucial moment for embedding these approaches into a durable and equitable system of information governance.

References

Ahmad, W., Sen, A., Eesley, C., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2024). Companies inadvertently fund online misinformation despite consumer backlash. Nature, 630(8015), 123-131. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07404-1

Altay, S., Lyons, B., & Modirrousta-Galian, A. (2023). Exposure to higher rates of false news erodes media trust and fuels overconfidence. OSF Preprint. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/t9r43

Bowles, J., Croke, K., Larreguy, H., Marshall, J., & Liu, S. (2023). Sustaining exposure to fact-checks: misinformation discernment, media consumption, and its political implications (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4582703). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4582703

Breuer, A. (2024). Information integrity and information pollution: Vulnerabilities and impact on social cohesion and democracy in Mexico (Discussion Paper 2/2024). German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). https://www.idos-research.de/discussion-paper/article/information-integrity-and-information-pollutionvulnerabilities-and-impact-on-social-cohesion-and-democracy-in-mexico/

Butler, L. H., Prike, T., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2024). Nudge-based misinformation interventions are effective in information environments with low misinformation prevalence. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62286-7

Carey, J. M., Guess, A. M., Loewen, P. J., Merkley, E., Nyhan, B., Phillips, J. B., & Reifler, J. (2022). The ephemeral effects of fact-checks on COVID-19 misperceptions in the United States, Great Britain and Canada. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(2), 236-243. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01278-3

Costello, T. H., Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. (2024). Durably reducing conspiracy beliefs through dialogues with AI. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xcwdn

EFCSN (European Fact-Checking Standards Network). (2024). Code of standards. European Fact-Checking Standards Network. https://efcsn.com/code-of-standards/

Garimella, K., & Chauchard, S. (2024). How prevalent is AI misinformation? What our studies in India show so far. Nature, 630(8015), 32-34. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01588-2

Green, Y. (2022, 12 December). Disinformation as a weapon of war: The case for prebunking. Friends of Europe. https://www.friendsofeurope.org/insights/disinformation-as-a-weapon-of-war-the-case-for-prebunking/

Hoes, E., Aitken, B., Zhang, J., Gackowski, T., & Wojcieszak, M. (2024). Prominent misinformation interventions reduce misperceptions but increase scepticism. Nature Human Behaviour, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01884-x

Iyengar, A., Gupta, P., & Priya, N. (2023). Inoculation against conspiracy theories: A consumer side approach to India’s fake news problem. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 37(2), 290-303. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3995

Kozyreva, A., Herzog, S. M., Lewandowsky, S., Hertwig, R., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Leiser, M., & Reifler, J. (2023). Resolving content moderation dilemmas between free speech and harmful misinformation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(7), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2210666120

Kozyreva, A., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Herzog, S. M., Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., Hertwig, R., Ali, A., BakColeman, J. . . . Wineburg, S. (2024). Toolbox of individual-level interventions against online misinformation. Nature Human Behaviour, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01881-0

Kreps, S., McCain, R. M., & Brundage, M. (2022). All the news that’s fit to fabricate: AI-generated text as a tool of media misinformation. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 9(1), 104-117. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.37

Maertens, R., Roozenbeek, J., Basol, M., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Long-term effectiveness of inoculation against misinformation: Three longitudinal experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000315

McCabe, S. D., Ferrari, D., Green, J., Lazer, D. M. J., & Esterling, K. M. (2024). Post-January 6th deplatforming reduced the reach of misinformation on Twitter. Nature, 630(8015), 132-140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07524-8

McPhedran, R., Ratajczak, M., Mawby, M., King, E., Yang, Y., & Gold, N. (2023). Psychological inoculation protects against the social media infodemic. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 5780. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32962-1

Mechkova, V., Pemstein, D., Seim, B., & Wilson, Steven. L. (2024). Measuring online political activity: Introducing the digital society project dataset. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2024.2350495

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). (2024). Development co-operation principles for relevant and effective support to media and the information environment. https://www.oecdilibrary.org/development/development-co-operation-principles-for-relevant-and-effective-support-to-media-andthe-information-environment_76d82856-en

Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592(7855), 590-595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

Pradel, F., Zilinsky, J., Kosmidis, S., & Theocharis, Y. (2024). Toxic speech and limited demand for content moderation on social media. American Political Science Review, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542300134X

Pretus, C., Javeed, A. M., Hughes, D., Hackenburg, K., Tsakiris, M., Vilarroya, O., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2024). The Misleading count: An identity-based intervention to counter partisan misinformation sharing. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, 379(1897), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2023.0040

Renault, T., Amariles, D. R., & Troussel, A. (2024). Collaboratively adding context to social media posts reduces the sharing of false news (arXiv:2404.02803). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.02803

UN (United Nations). (2023). Information integrity on digital platforms (Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 8, pp. 1-28). https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-information-integrity-en.pdf

UN Women. (2022). Accelerating efforts to tackle online and technology-facilitated violence against women and girls. https://shknowledgehub.unwomen.org/en/resources/accelerating-efforts-tackle-online-and-technologyfacilitated-violence-against-women-and

- (2024, 10 September). GDC Rev 3 – Draft under silence procedure. un.org: https://www.un.org/techenvoy/sites/www.un.org.techenvoy/files/general/GDC_Rev_3_silence_procedure.pdf

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2022). Information integrity: Forging a pathway to truth, resilience and trust. https://www.undp.org/publications/information-integrity-forging-pathway-truth-resilienceand-trust

Unver, A. (2020). Fact-checkers and fact-checking in Turkey (Cyber Governance and Digital Democracy). EDAM. https://edam.org.tr/en/cyber-governance-digital-democracy/fact-checkers-and-fact-checking-in-turkey

V-Dem Institute. (2024). Democracy Report 2024: Democracy winning and losing at the ballot. University of Gothenburg. https://v-dem.net/documents/43/v-dem_dr2024_lowres.pdf

World Economic Forum. (2024). Global risks report 2024. https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risksreport-2024