Email:[email protected]

Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

A number of emergent studies have examined COVID-19-induced behavioural responses, including shifts in consumption patterns (Kansiime et al., 2021; Pakravan-Charvadeh et al., 2021), impulsive purchasing (Naeem, 2020), stockpiling and panic buying episodes (Billore & Anisimova, 2021; Keane & Neal, 2021; Naeem, 2020; Prentice et al., 2021), brand and product substitutions (Knowles et al., 2020), and alterations in purchasing channel preferences (Mehrolia et al., 2021; Pantano et al., 2020). Scholars have attributed such behavioural phenomena to the pandemic’s effects on consumers’ socio-economic conditions, lifestyle disruptions, and challenges to pre-existing beliefs (Milaković, 2021), as well as to changes in the retail environment including stock shortages and supply chain interruptions (Prentice et al., 2021). Furthermore, external triggers such as information dissemination and social media exposure have been identified as influential factors shaping consumer responses (Laato et al., 2020; Naeem, 2020). Concomitantly, widespread job losses (Montenovo et al., 2020) and declines in household income (Kansiime et al., 2021) have exacerbated financial pressures. The pandemic has undermined consumers’ disposable income and affordability (Mahmud & Riley, 2021), transformed lifestyles (Sánchez-Sánchez et al.,2020), and heightened health-related awareness (Li et al., 2021). Collectively, these dynamics have compelled consumers to re-evaluate and adjust their spending practices compared to their pre-COVID-19 norms.

2. BACKGROUND LITERATURE

The transformations in consumer purchasing behaviour witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic align with the broader theoretical framework concerning shifts in consumer preferences and consumption patterns prompted by external disturbances—whether environmental, social, biological, cognitive, or behavioural (Mathur et al., 2006). Such large-scale disruptions typically drive consumers toward efforts to restore a sense of stability (Minton & Cabano, 2021), often leading to more deliberate and cautious behavioural tendencies (Sarmento et al., 2019). In times of economic uncertainty or downturn, this inclination toward stability frequently translates into austerity-driven behaviours, with heightened price sensitivity among consumers (Hampson & McGoldrick, 2013).Historical evidence reveals that pandemics, such as influenza outbreaks, have had marked impacts on economic functioning (Verikios et al., 2016). However, not all behavioural shifts can be solely ascribed to economic disruptions. For instance, during the Asian flu epidemic, consumers responded by engaging in risk-mitigation behaviours that influenced their consumption of poultry products (Yeung & Yee, 2012). Likewise, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, individuals residing in the affected U.S. Gulf Coast regions exhibited a blend of compulsive and impulsive purchasing, triggered by stress (Sneath et al., 2009). These extreme events also led to increased expenditures on luxury and premium goods, marked by both cross-category indulgences (Mark et al., 2016) and spontaneous purchasing impulses (Kennett-Hensel et al., 2012).

The present study is situated within this growing body of literature, focusing on two interrelated phenomena observed during the COVID-19 crisis: shifts in consumption patterns and product substitution behaviours. However, it differs from prior work in that it attributes these behavioural changes not solely to economic stimuli, but to the broader, multidimensional transformation in consumers’ lifestyles triggered by the pandemic. COVID-19 has altered both the volume and nature of consumer demand (del Rio-Chanona et al., 2020), leading to greater consumption of items that were previously marginal or absent in consumers’ typical purchase baskets (Kirk & Rifkin, 2020). These alterations represent what we define as “new demand”—a substantial, pandemic-induced shift in market consumption patterns. Examples include heightened demand for disinfectants and personal hygiene products such as hand sanitizers and disinfectant sprays (Chaudhuri, 2020), as well as wellness-related goods like vitamins, health supplements, and immunity-boosting foods (Hess, 2020). Additional categories experiencing surges include packaged consumables, household cleaning agents, organic and fresh food items, personal care products (Knowles et al., 2020), and digital service platforms (Debroy, 2020).

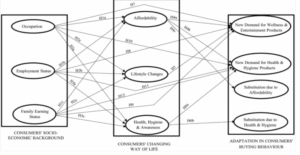

3. THEORETICAL MODEL AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

3.1. Consumers’ socio-economic background and affordability

The COVID-19 crisis has markedly affected household and individual incomes, subsequently influencing spending capacities. Nevertheless, the magnitude and character of these financial strains have varied considerably by occupation, employment stability, and broader socio-demographic factors (Witteveen, 2020). The most pronounced negative outcomes have been observed among occupations characterised by lower educational attainment, reduced skill requirements, limited remote work feasibility (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020), and higher dependence on face-to-face interaction (Avdiu & Nayyar, 2020; Montenovo et al., 2020). Many individuals reported earning less than their typical wages during lockdown periods, while others experienced job loss altogether, diminishing their ability to maintain pre-pandemic household expenditures. Prior studies have demonstrated that household purchasing power was mediated by family income levels, accumulated savings, and occupational standing (Kansiime et al., 2021; Pakravan-Charvadeh et al., 2021; Piyapromdee & Spittal, 2020). Moreover, the number of income-contributing family members is a critical determinant of a household’s economic resilience and spending capacity (Addabbo, 2000). Based on these observations, we propose the following hypotheses:

3.2. Consumers’ socio-economic background and lifestyle modifications

The pandemic has also precipitated profound transformations in consumers’ lifestyles, though the extent and nature of these changes differ across socio-economic groups. For instance, individuals working in sectors such as hospitality, travel, and Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) have experienced sharp declines in business activity and income. By contrast, employees in other sectors, particularly those able to work remotely, often perceived the period as an opportunity to step back from otherwise demanding routines. This suggests that occupational characteristics play an important role in shaping individuals’ daily schedules and lifestyle adjustments during crises. Prior

3.3. Consumers’ socio-economic background and awareness of health and hygiene

Hypothesis 3a

Hypothesis 3b

Hypothesis 3c

3.4. Affordability and consumers’ buying behaviour

Hypothesis 4a

Hypothesis 4b

Hypothesis 4c

3.5. Lifestyle changes and demand for wellness and entertainment products

Hypothesis 5

3.6. Awareness of health and hygiene and demand for health and hygiene products

Marketing scholars have consistently underscored the role of raising consumer awareness to stimulate demand for relevant products (Baiano et al., 2020; Hess, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly heightened individuals’ attention to their personal health and hygiene practices. As an essential component of a healthy lifestyle, frequent handwashing and the use of protective face masks have come to be regarded as critical defence measures against viral transmission. Consequently, ordinary consumers have allocated increased portions of their expenditures to healthcare-related products (Rakshit, 2020). Furthermore, there has been a remarkable shift in attitudes, as many consumers

Hypothesis 6a

Hypothesis 6b

3.7. Consumers’ socio-economic background and creation of new demand for wellness and entertainment products

Hypothesis 7

Hypothesis 8

Hypothesis 9

Hypothesis 10

Hypothesis 11

Hypothesis 12

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

4.1. Design of the Survey Instrument and Its Reliability

Among the selected respondents, certain individuals were proficient in Hindi, others in Malayalam, and a few in Bengali. For participants employed in the Public and Private Sectors, the questionnaire was distributed via email, requesting clear and prompt responses within one week. In the case of MSME employees and independent business owners, appointments were arranged telephonically, and one of the authors conducted face-to-face interviews while adhering strictly to social distancing protocols. Data collection in Delhi and Kozhikode was carried out independently by authors based in those respective locations. For the daily wage earners—including rickshaw-pullers, street vendors, and masons—the questions were posed verbally, and their responses were captured through audio recordings that were later transcribed for analysis.

Following the compilation of responses from this preliminary phase, we systematically synthesised the findings into thematic sections and designed a second open-ended questionnaire. The principal aim of this second iteration was to verify content coverage with domain experts and ensure that each item accurately represented its intended construct, thereby strengthening content validity. For example, items capturing dimensions of financial distress due to the pandemic were classified under the construct of ‘Affordability’. Expert reviewers were then asked to assess whether these items sufficiently conveyed the essence of affordability as experienced by consumers.

TABLE 1.

|

Variable |

Percentage of respondents (%) |

Variable |

Percentage of respondents (%) |

|

Gender |

|

Job profile |

|

|

Male |

71.53 |

Government or Public Sector |

22.35 |

|

Female |

28.47 |

Private Firm |

27.53 |

|

Age |

|

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, contractors and Daily Wage-earners |

28.00 |

|

24–35 years |

54.59 |

Independent Businesses |

7.06 |

|

45–55 years |

33.65 |

Others |

15.06 |

|

56–65 years |

10.59 |

Employment status |

|

|

66 years and above |

1.18 |

Employed and getting full salary |

51.53 |

|

Educational background |

Employed and getting reduced salary |

23.29 |

|

|

Graduates in a non- professional course |

13.88 |

Lost job due to lockdown |

12.47 |

|

|

|

Others |

12.50 |

|

Graduates in a professional course |

56.00 |

Family earning status |

|

|

|

|

Sole Earning Member |

29.88 |

|

School Board or No Formal Education |

25.64 |

Multiple Earning Member |

55.29 |

|

Others |

4.47 |

Non-earning Member |

14.82 |

4.2 Target respondents and data collection procedure

Given the lockdown measures and restrictions on physical mobility imposed during the pandemic, a combination of approaches was adopted to reach potential respondents. Specifically, both online and offline modes were utilised for administering the questionnaire. For the online distribution, the survey link was shared via popular social media platforms, namely LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Facebook, appealing to users to participate in the study. These platforms were selected not only due to their widespread popularity in India but also because the research team maintained active professional and social networks on these channels.

4.3 Assessment of potential biases in the survey data

5. DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

5.1. Demographic profile

5.2. Confirmatory factor analysis

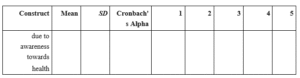

The questionnaire, developed through an iterative, expert-validated process, facilitated the identification of underlying latent constructs. It was established that Consumers’ changing way of life comprised three constructs, whereas Adaptation in consumers’ buying behaviour encompassed four constructs. CFA was implemented to examine the degree to which the observed variables—namely, 13 items related to Consumers’ changing way of life

TABLE 2.

|

Construct |

Mean |

SD |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. Affordability |

2.985 |

1.614 |

0.842 |

– |

|

|

|

|

|

2. Life-style Changes |

3.147 |

1.376 |

0.645 |

−0.282*** |

– |

|

|

|

|

3. Awareness towards health & hygiene |

4.458 |

0.862 |

0.736 |

−0.181** |

0.567*** |

– |

|

|

|

4. Creation of new demand for wellness & entertainment products |

4.29 |

0.927 |

0.816 |

−0.102* |

0.616*** |

0.281*** |

– |

|

|

5. Creation of new demand for health & hygiene products |

2.114 |

1.235 |

0.801 |

−0.170** |

0.324*** |

0.405*** |

0.252*** |

– |

|

6. Substitution of daily necessities due to affordability |

2.239 |

1.118 |

0.803 |

−0.197*** |

0.321*** |

0.187** |

0.408*** |

0.149* |

|

7. Substitution of daily necessities |

2.856 |

1.248 |

0.817 |

−0.169** |

0.440*** |

0.197*** |

0.272*** |

0.243* |

TABLE 3.

|

Construct |

Observable item |

Standardized Loading |

T–value |

AVE |

CR |

|

Affordability |

|

|

|

0.648 |

0.846 |

|

|

Restricted economic |

0.752 |

15.256 |

|

|

|

|

activity arising out of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 has resulted in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

significant reduction of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

my regular income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Restricted economic |

0.881 |

16.212 |

|

|

|

|

activity arising out of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 has resulted in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

significant reduction of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

my savings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Restricted economic |

0.777 |

a |

|

|

|

|

activity arising out of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 has reduced |

|

|

|

|

|

|

my ability to meet the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

day-to-day household |

|

|

|

|

|

|

expenses |

|

|

|

|

|

Lifestyle changes |

|

|

|

0.477 |

0.646 |

|

|

The spread of Covid-19 |

0.707 |

a |

|

|

|

|

has forced me and my |

|

|

|

|

|

|

family-members to do |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yoga/Physical exercise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

on regular basis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The spread of Covid-19 |

0.674 |

10.301 |

|

|

|

|

has renewed our |

|

|

|

|

|

|

interest towards the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

importance of herbal |

|

|

|

|

|

Construct |

Observable item |

Standardized Loading |

T–value |

AVE |

CR |

|

|

products in our day-to- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

day life |

|

|

|

|

|

Awareness towards |

|

|

|

0.504 |

0.752 |

|

health & hygiene |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The spread of Covid-19 |

0.769 |

a |

|

|

|

|

has increased the level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

of awareness of the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

health of my family |

|

|

|

|

|

|

members including me |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The spread of Covid-19 |

0.712 |

9.573 |

|

|

|

|

has increased the level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

of awareness of my |

|

|

|

|

|

|

family members |

|

|

|

|

|

|

including me about |

|

|

|

|

|

|

maintaining cleanliness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

and hygiene |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The spread of Covid-19 |

0.643 |

8.363 |

|

|

|

|

has increased the level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

of awareness of my |

|

|

|

|

|

|

family members |

|

|

|

|

|

|

including me about the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

adoption of safety |

|

|

|

|

|

|

measures in terms of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

using masks and gloves |

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new |

|

|

|

0.553 |

0.827 |

|

demand for wellness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

& entertainment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

products |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new demand |

0.526 |

a |

|

|

|

|

for Herbal products for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

external use due to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

Construct |

Observable item |

Standardized Loading |

T–value |

AVE |

CR |

|

|

Creation of new demand |

0.792 |

9.865 |

|

|

|

|

for subscription to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

channels of Art of living |

|

|

|

|

|

|

lessons due to Covid-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new demand |

0.888 |

10.018 |

|

|

|

|

for subscription to Yoga |

|

|

|

|

|

|

channels due to Covid- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new demand |

0.720 |

9.515 |

|

|

|

|

for subscription to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fitness channels due to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new |

|

|

|

0.605 |

0.820 |

|

demand for health & |

|

|

|

|

|

|

hygiene products |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new demand |

0.688 |

a |

|

|

|

|

for liquid hand-wash |

|

|

|

|

|

|

due to Covid-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new demand |

0.854 |

13.821 |

|

|

|

|

for hand sanitizer due to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of new demand |

0.782 |

13.614 |

|

|

|

|

for masks due to Covid- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

Substitution of daily |

|

|

|

0.612 |

0.823 |

|

necessities due to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

affordability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substitution of |

0.719 |

a |

|

|

|

|

Expensive staple food |

|

|

|

|

|

|

items with the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inexpensive staple food |

|

|

|

|

|

|

items |

|

|

|

|

|

Construct |

Observable item |

Standardized Loading |

T–value |

AVE |

CR |

|

Substitution of daily necessities due to awareness towards health |

Substitution of Expensive Fast moving consumer goods with the Inexpensive Fast moving consumer goods |

0.934 |

15.521 |

0.640 |

0.839 |

|

Substitution of Expensive packaged food with the Inexpensive packaged food |

0.669 |

13.74 |

|||

|

Substitution of Conventional staple food items with the Healthy staple food items |

0.793 |

a |

|||

|

Substitution of Conventional Fast moving consumer goods with the Organic (Non- toxic) Fast moving consumer goods |

0.931 |

18.147 |

|||

|

Substitution of Conventional Packaged food with the Organic food |

0.651 |

14.671 |

Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; CR, construct reliability.

Convergent validity refers to the extent to which the indicator variables of a construct share a substantial proportion of variance. It was evaluated in this study using two distinct approaches. The first approach entailed examining the estimated factor loadings of each item on the respective constructs within the final Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The analysis revealed that the standardized loadings of all items exceeded 0.5 and were statistically significant (p < .001). The second approach assessed convergent validity by calculating the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). An AVE of 0.5 or higher signifies a high degree of convergent validity (Hair et al., 2009). As presented in Table 3, the AVE values for the seven constructs ranged between 0.477 and 0.648. Six constructs attained AVE scores above the 0.5 threshold, indicating strong convergent validity. Only the construct pertaining to lifestyle changes displayed an AVE marginally below the recommended cutoff. However, because this construct satisfied the convergent validity criteria based on the first approach, and given that its AVE value was only slightly under the threshold, it may still be regarded as possessing an acceptable degree of convergent validity.

5.3. Structural Equation Modelling

6. MAJOR FINDINGS

6.1. Influence of Occupation, Employment Status, and Earning Status on Affordability

The socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the respondents, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate notable differences in occupation, current employment status, and earning status. Respondents were classified into five occupational categories, labelled Job1 through Job5. Regarding employment status, four categories were defined and denoted as Emp1 through Emp4. Additionally, respondents were grouped into three categories based on their family earning capacity, designated Earn1 through Earn3. These categorical distinctions aredetailed in Table 4. Before incorporating these variables as exogenous predictors in the structural model, all categorical variables were individually converted into binary variables. Consistent with the approach outlined by Cohen et al. (2003), Job1, Emp1, and Earn2 were selected as the reference categories for occupation, employment status, and earning status, respectively. These reference categories were chosen as each represented the most prevalent group within their socio-economic classifications and were presumed to be the least adversely affected by the pandemic.

In relation to Hypothesis 1b, which assessed the link between current employment status and affordability, the results reveal a significant negative impact on the affordability of individuals within employment categories Emp2 through Emp4 compared to respondents in Emp1. This provides clear evidence that individuals who had lost their employment or were receiving reduced salaries as a consequence of COVID 19 experienced substantially diminished affordability relative to their counterparts who continued to receive their full salaries. With respect to Hypothesis 1c, which explored the relationship between family earning status and affordability, the results indicate that respondents in Earn1 and Earn3 did not experience significantly different impacts on affordability relative to the reference category, Earn2. This suggests that whether a household had a single earning member,

TABLE 4.

Results of structural model for socio‐economic factors (direct effects) (n = 425)

| Hypothesis | Structural path | β | t‐value | p‐value | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1a | Job2 → Affordability | −0.040 | −0.669 | .503 | Not supported |

| Job3 → Affordability | −0.226 | −3.387 | *** | Supported in opposite direction | |

| Job4 → Affordability | −0.013 | −0.241 | .809 | Not supported | |

| Job5 → Affordability | −0.136 | −2.060 | .039* | Supported in opposite direction | |

| Hypothesis 1b | Emp2 → Affordability | −0.261 | −4.722 | *** | Supported in opposite direction |

| Emp3 → Affordability | −0.368 | −6.462 | *** | Supported in opposite direction | |

| Emp4 → Affordability | −0.212 | −3.273 | .001*** | Supported in opposite direction | |

| Hypothesis 1c | Earn1 → Affordability | 0.029 | 0.577 | .564 | Not supported |

| Earn3 → Affordability | 0.052 | 0.900 | .368 | Not supported | |

| Hypothesis 2a | Job2 → Lifestyle changes | −0.178 | −2.301 | .021* | Supported in opposite direction |

| Job3 → Lifestyle changes | −0.198 | −2.306 | .021* | Supported in opposite direction | |

| Job4 → Lifestyle changes | −0.140 | −1.969 | .049* | Supported in opposite direction | |

| Job5 → Lifestyle changes | −0.141 | −1.659 | .097† | Supported in opposite direction | |

| Hypothesis 2b | Emp2 → Lifestyle changes | 0.190 | 2.676 | .007** | Supported |

| Emp3 → Lifestyle changes | 0.251 | 3.469 | *** | Supported | |

| Emp4 → Lifestyle changes | 0.054 | 0.658 | .511 | Not supported | |

| Hypothesis 2c | Earn1 → Lifestyle changes | −0.087 | −1.365 | .172 | Not supported |

| Earn3 → Lifestyle changes | 0.042 | 0.554 | .579 | Not supported | |

| Hypothesis 3a | Job2 → Awareness towards health | −0.150 | −2.024 | .043* | Supported in opposite direction |

| Job3 → Awareness towards health | −0.052 | −0.641 | .521 | Not supported | |

| Job4 → Awareness towards health | −0.101 | −1.489 | .137 | Not supported | |

| Job5 → Awareness towards health | −0.125 | −1.537 | .124 | Not supported | |

| Hypothesis 3b | Emp2 → Awareness towards health | 0.084 | 1.253 | .210 | Not supported |

| Emp3 → Awareness towards health | 0.097 | 1.430 | .153 | Not supported | |

| Emp4 → Awareness towards health | 0.030 | 0.380 | .704 | Not supported | |

| Hypothesis 3c | Earn1 → Awareness towards health | −0.017 | −0.276 | .783 | Not supported |

| Earn3 → Awareness towards health | 0.054 | 0.758 | .449 | Not supported |

Job1: Respondents who are working in government or public sector jobs; Job2: Respondents who are working in private sector jobs; Job3: Respondents who are working in MSME sectors/ Contractors/ Daily wage earners;

Job4: Respondents who own their own business or startups; Job5: Respondents with other job profiles.

Emp1: Respondents who are currently employed and getting full salary; Emp2: Respondents who are currently employed but are getting reduced salary; Emp3: Respondents who have lost their jobs during lockdown; Emp4: Respondents with other employment status;

Earn1: Respondents who are the sole earners of the family; Earn2: Respondents who are one of the earning members of the family; Earn3: Respondents who are the non‐earning members of the family.

†

p < .10.

*

p < .05

**

p < .01

***

p < .001.

|

Hypothesis |

Structuralpath |

β |

t–value |

p–value |

Comments |

|

Hypothesis2c |

Emp4 → Lifestyle changes |

0.054 |

0.658 |

.511 |

Notsupported |

|

Earn1 → Lifestyle changes |

−0.087 |

−1.365 |

.172 |

Notsupported |

|

|

|

Earn3 → Lifestyle changes |

0.042 |

0.554 |

.579 |

Notsupported |

|

Hypothesis3a |

Job2 → Awareness towards health |

−0.150 |

−2.024 |

.043* |

Supported in opposite direction |

|

|

Job3 → Awareness towards health |

−0.052 |

−0.641 |

.521 |

Notsupported |

|

|

Job4 → Awareness towards health |

−0.101 |

−1.489 |

.137 |

Notsupported |

|

|

Job5 → Awareness towards health |

−0.125 |

−1.537 |

.124 |

Notsupported |

|

Hypothesis3b |

Emp2 → Awareness towards health |

0.084 |

1.253 |

.210 |

Notsupported |

|

|

Emp3 → Awareness towards health |

0.097 |

1.430 |

.153 |

Notsupported |

|

|

Emp4 → Awareness towards health |

0.030 |

0.380 |

.704 |

Notsupported |

|

Hypothesis3c |

Earn1 → Awareness towards health |

−0.017 |

−0.276 |

.783 |

Notsupported |

|

Earn3 → Awareness towards health |

0.054 |

0.758 |

.449 |

Notsupported |

TABLE 5.

Results of structural model of consumers’ way of life (direct effects) (n = 425)

|

Hypothesis |

Structural Path |

β |

t-value |

p-value |

Comments |

|

Hypothesis 4a |

Affordability → Demand for wellness products |

−0.092 |

−1.559 |

.119 |

Not supported |

|

Hypothesis 4b |

Affordability → Demand for health products |

−0.104 |

−1.645 |

.110 |

Not supported |

|

Hypothesis 4c |

Affordability → Substitution of affordable necessities |

−0.167 |

−3.079 |

.002** |

Supported |

|

Hypothesis 5 |

Lifestyle changes → Demand for wellness products |

0.635 |

6.434 |

*** |

Supported |

|

Hypothesis 6a |

Awareness towards health → Demand for health products |

0.402 |

5.822 |

*** |

Supported |

|

Hypothesis 6b |

Awareness towards health → Substitution of healthy necessities |

0.227 |

3.673 |

*** |

Supported |

** p < .01

*** p < .001.

6.2. Influence of Occupation, Employment Status, and Earning Status on Lifestyle Changes

Applying a comparable analytical approach, we examined how occupation, current employment status, and earning status affected lifestyle changes among individuals in the context of COVID-19. The results pertaining to Hypothesis 2a, which explored the association between occupation and lifestyle adjustments, demonstrated that individuals categorized under Job2 through Job5 exhibited lifestyle changes that were significantly different in direction compared to those in the reference group, Job1. This pattern suggests that individuals outside government or public sector employment were less likely to adopt lifestyle modifications during the pandemic.In relation to Hypothesis 2b, which investigated the connection between employment status and lifestyle changes, findings indicated that respondents within Emp2 and Emp3 categories experienced significantly positive lifestyle changes relative to the reference group, Emp1. This evidence implies that individuals who either lost their employment or faced reduced income became more engaged in activities such as practicing yoga and integrating herbal products into their daily routines compared to those who continued to receive full salaries.

6.4. Association of Affordability, Lifestyle Changes, and Health Awareness with Demand for Wellness and Health Products and Substitution of Affordable Necessities

6.5. Influence of Occupation on Demand for Wellness Products

TABLE 6.

Hypothesis 7 Influence of occupation on the demand for wellness products (direct, indirect and

total effects) (n = 425)

| Structural path | Direct effect | Specific indirect effect | Total indirect effect | Total direct & indirect effect | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | p‐value | β | p‐value | β | p‐value | β | p‐value | ||

| Job3 → Demand for wellness product | −0.022 | 0.753 | Direct effect is negative & insignificant while the total indirect effect is negative & significant at 10% level. Total direct and indirect effect is negative & significant at 10% level. (Partial mediation) | ||||||

| Job3 → Affordability → Demand for wellness product | 0.021 | 0.095 | |||||||

| Job3 → Lifestyle changes → Demand for wellness product | −0.126 | .014 | −0.105 | .077 | −0.127 | .069 | |||

TABLE 7.

Hypothesis 9 Influence of earning status on the demand for wellness products (direct, indirect and total effects) (n = 425)

| Structural path | Direct effect | Specific indirect effect | Total indirect effect | Total direct & indirect effect | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | p‐value | β | p‐value | β | p‐value | β | p‐value | ||

| Earn1 → Demand for wellness product | −0.062 | .233 | Direct effect is negative and insignificant while total indirect effect is also negative and insignificant. However, total direct and indirect effect is negative and significant at 5% level (Full mediation) | ||||||

| Earn1 → Affordability → Demand for wellness product | −0.003 | .393 | |||||||

| Earn1 → Lifestyle changes Demand for wellness product | −0.056 | .212 | −0.059 | 0.214 | −0.121 | .047 | |||

| Earn3 → Demand for wellness product | −0.074 | .228 | Direct effect is negative and insignificant while total indirect effect is positive and insignificant. However, total direct & indirect effect is negative and insignificant. | ||||||

| Earn3 → Affordability → Demand for wellness product | −0.005 | .263 | |||||||

| Earn3 → Lifestyle changes → Demand for wellness product | 0.026 | .58 | 0.021 | 0.652 | −0.053 | .409 | |||

TABLE 8.

Hypothesis 11 Influence of emp. Status on the creation of new demand for health products (direct, indirect and total effects) (n = 425)

| Structural path | Direct effect | Specific indirect effect | Total indirect effect | Total direct & indirect effect | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p‐value | β | p‐value | β | p‐value | β | p‐value | ||

| Emp3 → Demand for health products | 0.095 | 0.137 | Direct effect is positive & insignificant while total indirect effect is positive & significant at 5% level. The total direct & indirect effect is positive and significant at 1% level. (Partial mediation) | ||||||

| Emp3 → Affordability → Demand for health product | 0.038 | .137 | |||||||

| Emp3 → Awareness towards health → Demand for health product | 0.039 | .211 | 0.077 | .049 | 0.172 | .004 | |||

TABLE 9.

Hypothesis 12 Influence of earning status on the creation of new demand for health products (direct, indirect and total effects) (n = 425)

|

Structural path |

Direct effect |

Specific indirect effect |

Total indirect effect |

Total direct & indirect effect |

Com |

||||

|

β |

p–value |

β |

p–value |

β |

p–value |

β |

p–value |

||

|

Earn1 → Demand for health product |

−0.076 |

.155 |

|

|

−0.010 |

.731 |

−0.086 |

.195 |

Dire is ne insig whil indir effec nega insig The direc indir effec nega insig |

|

Earn1 → Affordability → Demand for health product |

|

|

−0.003 |

.436 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Earn1 → Awareness towards health → Demand for health product |

|

|

−0.007 |

.767 |

|||||

|

Earn3 → Demand for health product |

0.111 |

.081 |

|

|

Dire is po and signi 10% whil indir effec posi insig |

||||

|

Earn3 → Affordability → Demand for health product |

|

|

−0.005 |

.263 |

|||||

|

Structural path |

Direct effect |

Specific indirect effect |

Total indirect effect |

Total direct & indirect effect |

Com |

||||

|

β |

p–value |

β |

p–value |

β |

p–value |

β |

p–value |

||

|

Earn3 → Awareness towards health → Demand for health product |

|

|

0.022 |

.468 |

0.017 |

.546 |

0.128 |

.05 |

The direc indir effec posi signi 5% l (Par med |

6.6. Influence of Employment Status and Earning Status on the Demand for Wellness Products

We examined the outcomes of Hypothesis 8, which assessed the impact of current employment status on the demand for wellness and entertainment products, treating Emp1 as the reference group. The analysis revealed that employment status categories Emp2, Emp3, and Emp4 did not exert any statistically significant influence on the creation of new demand for wellness and entertainment products relative to the reference category. Given the lack of significant findings across all employment status categories, we have chosen not to report these results in detail.

Turning to Hypothesis 9, we evaluated the role of family earning status in shaping demand for wellness products, with Earn2 designated as the reference category. These findings are presented in Table 7. The results demonstrated that respondents belonging to earning status category Earn1 exhibited a significant negative effect on the generation of new demand for wellness and entertainment products compared to the reference group. This relationship was mediated by two intervening constructs: (1) change in affordability and (2) lifestyle changes. Notably, the mediation was identified as full, implying that the indirect pathways entirely explained the association between earning status and demand.

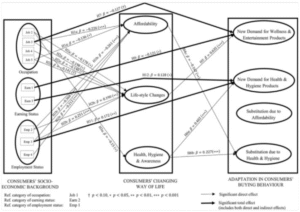

In contrast, the earning status of individuals in category Earn3 did not have any significant impact on demand for wellness and entertainment products relative to the reference category. Figure 2 visually highlights the significant effect of Hypothesis 9, illustrating the influence of earning status category Earn1 on demand for wellness and entertainment products.

6.7. Influence of Occupation, Employment Status, and Earning Status on the Demand for Health Products

Next, we analysed the role of occupational categories in driving demand for health and hygiene products, again designating Job1 as the reference category. The analysis indicated that occupations classified under Job2 through Job5 did not demonstrate any significant effect on the creation of new demand for health and hygiene products compared to the reference group. Accordingly, we have opted not to report the detailed outcomes of Hypothesis 10.

Subsequently, we assessed Hypothesis 11, which investigated the influence of employment status on the emergence of demand for health and hygiene products, with Emp1 as the reference category. The results revealed that respondents in employment status category Emp3 experienced a significant positive effect on the creation of new demand for health and hygiene products relative to the reference group. This association was mediated by two constructs: (1) change in affordability and (2) increased awareness toward health and hygiene. The mediation was identified as partial, indicating that both direct and indirect pathways contributed to the observed relationship.

Conversely, employment statuses corresponding to categories Emp2 and Emp4 did not exhibit any significant impact on demand for health and hygiene products compared to Emp1. Table 8 details the findings for Hypothesis 11 regarding employment status category Emp3 exclusively. Furthermore, Figure 2 displays the cumulative significant effect of employment status category Emp3 on demand for health and hygiene products.

Finally, we examined Hypothesis 12, which focused on the impact of family earning status on the creation of demand for health and hygiene products, using Earn2 as the reference category. As shown in Table 9, the results indicated that respondents in earning status category Earn3 reported a significant positive effect on the emergence of new demand for health and hygiene products relative to the reference group. This association was mediated by (1) change in affordability and (2) heightened awareness toward health and hygiene, with mediation identified as partial. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the total significant effect of Hypothesis 12 for earning status category Earn3.

In contrast, individuals within earning status category Earn1 did not exhibit any significant influence on demand for health and hygiene products compared to the reference category.

8. CONCLUSION

This paper presented a questionnaire-based investigation aimed at examining the impact of COVID-19 on consumers’ affordability, lifestyle adjustments, and health awareness, as well as how these factors collectively shaped purchasing behaviour. The analysis of the collected data brought to light several noteworthy insights regarding the pandemic’s consequences and consumers’ responses. Among the principal findings are: (1) COVID-19 exerted a greater adverse impact on the affordability of individuals employed in unorganised sectors relative to those in organised sectors, (2) the type of occupation, current employment status, and family earning capacity each exerted varying degrees of influence on lifestyle transformations experienced by consumers, and (3) health awareness was found to be significantly higher among respondents who had either lost employment or whose families had lower earning potential.

The study further observed that demand for wellness and entertainment products was driven more by lifestyle changes than by affordability constraints, while demand for health and hygiene products was predominantly influenced by heightened health consciousness. Conversely, affordability primarily determined consumers’ propensity to seek affordable substitutes for daily necessities. As such, these findings can serve as a valuable reference point for exploring how disruptive events precipitate shifts in consumption and substitution behaviour. Moreover, the results provide actionable insights for organisations seeking to develop appropriate strategies to address changing consumer needs and preferences in the wake of a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations inherent in this research. The staggered imposition of lockdowns across different Indian regions presented logistical challenges to administering the survey. Additionally, the vast geographic and cultural diversity of India constrained the study’s reach, limiting the inclusion of all social and demographic groups. A broader reach would likely have yielded further nuanced perspectives on consumer behaviour and opportunities for more detailed market segmentation. Furthermore, the research scope was confined to wellness, entertainment, and health-related products, as well as daily necessities. Future studies could extend the scope to encompass a broader range of product categories, which would enhance understanding of marketing strategies under conditions of disruption.

Drawing on the observations of Paul and Bhukya (2021), the present research invites several avenues for future exploration. These include: (1) conducting cross-national studies to examine how pandemic-related disruptions have influenced consumer behaviour across cultural, regional, and generational divides, (2) investigating how firms adapt their practices and offerings in response to evolving consumer needs during crises, and (3) assessing how shifts in consumption patterns inform retailers’ decisions regarding product assortments, channel strategies, promotional tactics, and discounting practices. It is anticipated that these strategies will vary according to factors such as a retailer’s geographic location, scale of operations, and target customer segments.

Finally, given that government interventions—such as relief schemes, subsidies, and other forms of aid—played a critical role in shaping consumers’ experiences during the pandemic, an important direction for future research would be to examine how such measures helped mitigate negative outcomes for households while also supporting the long-term viability of businesses.

APPENDIX 1. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF FACTORS INFLUENCING CONSUMERS’ CHANGING WAY OF LIFE

|

Factors influencing consumers’ changing way of life |

Min. score |

Max. score |

Mean |

SD |

|

Affordability |

|

|

|

|

|

(1) Not at all True (2) Scarcely True (3) Somewhat True (4) Considerably True (5) Absolutely True |

|

|

|

|

|

Restricted economic activity has resulted in significant reduction in my regular income a |

1 |

5 |

2.73 |

1.70 |

|

Restricted economic activity has resulted in significant reduction in my savings a |

1 |

5 |

2.96 |

3.27 |

|

Restricted economic activity has reduced my ability to meet the day-to-day household expenses a |

1 |

5 |

1.59 |

1.54 |

|

Lifestyle changes |

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 has forced me and my family-members to change our daily routine b |

1 |

5 |

3.87 |

1.19 |

|

Covid-19 has forced me and my family-members to do Yoga/Physical exercise on regular basis b |

1 |

5 |

3.01 |

1.39 |

|

Covid-19 has renewed our understanding towards the importance of herbal products in our day-to- day life |

1 |

5 |

3.28 |

1.37 |

|

I have more free time now than it used to be earlier b |

1 |

5 |

3.45 |

1.48 |

|

Awareness towards health and hygiene |

|

|

|

|

|

Covid-19 has increased the level of awareness of my own health and the health of my family members |

1 |

5 |

4.21 |

1.03 |

|

Covid−19 has increased the level of awareness of me and my family members about cleanliness and hygiene |

1 |

5 |

4.42 |

0.90 |

|

Covid-19 has increased the level of awareness of me and my family members about the adoption of |

1 |

5 |

4.74 |

0.59 |

|

Factors influencing consumers’ changing way of life |

Min. score |

Max. score |

Mean |

SD |

|

safety measures in terms of using masks and gloves Covid-19 has made me sensitive to what I should eat b |

1 |

5 |

3.44 |

1.39 |

|

Covid-19 has allowed me to get online appointment of Doctor very easily b |

1 |

5 |

3.55 |

1.56 |

|

Covid-19 has allowed me to get hassle-free online consultation of the Doctor through video-call b |

1 |

5 |

2.29 |

1.24 |

| Adaptation in consumers’ buying behaviour | Min. score | Max. score | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creation of new demand for products relating to health and hygiene | ||||

| (1) Very low (2) Low (3) Moderate (4) High (5) Very High | ||||

| Liquid hand wash | 1 | 5 | 4.13 | 0.98 |

| Hand sanitizer | 1 | 5 | 4.31 | 0.93 |

| Masks | 1 | 5 | 4.42 | 0.87 |

| Gloves a | 1 | 5 | 3.10 | 1.39 |

| Immunity booster supplements a | 1 | 5 | 3.13 | 1.41 |

| (Vitamin C, Zinc, Ayurveda formulations etc.) | ||||

| Creation of new demand for products relating to wellness and entertainment | ||||

| (1) Never (2) Rarely (3) Sometimes (4) Often (5) Always | ||||

| Herbal products for external use | 1 | 5 | 2.55 | 1.29 |

| Subscription to Art of living lessons | 1 | 5 | 1.80 | 1.12 |

| Subscription to Yoga channels | 1 | 5 | 1.98 | 1.20 |

| Subscription to Fitness channels | 1 | 5 | 2.12 | 1.32 |

| Subscription Web‐series channels a | 1 | 5 | 2.77 | 1.59 |

| Substitution due to affordability | ||||

| (1) Very low (2) Low (3) Moderate (5) High (5) Very high | ||||

| Substitution of Expensive staple food (Rice, Ata, Pulses, sugar, salt, edible oil, spices etc.) with the Inexpensive staple food | 1 | 5 | 2.22 | 1.09 |

| Substitution of Expensive Fast‐moving consumer goods (FMCG) (Soap, detergent, shampoo, toothpaste, disinfectants etc.) with the Inexpensive FMCG | 1 | 5 | 2.28 | 1.10 |

| Substitution of Expensive Packaged food (Noodles, pasta, pizza base, bread, canned soups, Tomato sauce, Frozen food, oats, soft drinks, biscuits etc.) with the Inexpensive one | 1 | 5 | 2.22 | 1.17 |

| Substitution due to awareness towards health | ||||

| (1) Very low (2) Low (3) Moderate (5) High (5) Very high | ||||

| Substitution of Conventional staple food (Rice, Ata, Pulses, sugar, salt, edible oil, spices etc.) with the Healthy staple food | 1 | 5 | 2.84 | 1.20 |

| Substitution of Conventional FMCG (Soap, detergent, shampoo, toothpaste, disinfectants etc.) with the Organic (Non‐toxic) FMCG | 1 | 5 | 2.82 | 1.22 |

| Substitution of Conventional Packaged food (Noodles, pasta, pizza base, bread, canned soups, Tomato sauce, Frozen food, oats, soft drinks, biscuits etc.) with the Healthy one | 1 | 5 | 2.90 | 1.32 |

a

The items have been dropped while carrying out Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Das, D. , Sarkar, A. , & Debroy, A. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on changing consumer behaviour: Lessons from an emerging economy. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 46, 692–715. 10.1111/ijcs.12786

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors declare that the data used in the paper is collected through a questionnaire survey and have not used any proprietary data from any source. The data collected through the primary survey may be made available on demand.

REFERENCES

- Adams-Prassl, A. , Boneva, T. , Golin, M. , & Rauh, C. (2020, April 1). Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: New survey evidence for the UK. Cambridge-INET Working Paper Series. IZA Institute of Labor Economics. [Google Scholar ]

- Addabbo, T. (2000). Poverty dynamics: Analysis of household incomes in Italy. Labour, 14(1), 119–144. 10.1111/1467-9914.00127 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, J. C. , & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Arora, T. , & Grey, I. (2020). Health behaviour changes during COVID-19 and the potential consequences: A mini-review. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(9), 1155–1163. 10.1177/1359105320937053 [DOI ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Aunger, R. , Greenland, K. , Ploubidis, G. , Schmidt, W. , Oxford, J. , & Curtis, V. (2016). The determinants of reported personal and household hygiene behaviour: A multi-country study. PLoS One, 11(8), e0159551. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159551 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Avdiu, B. , & Nayyar, G. (2020). When face-to-face interactions become an occupational hazard: Jobs in the time of COVID-19. Economics Letters, 197, 109648. [Google Scholar ]

- Baiano, C. , Zappullo, I. , & Conson, M. (2020). Tendency to worry and fear of mental health during Italy’s COVID-19 lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5928. 10.3390/ijerph17165928 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Bakhtiani, G. (2021). How the wellness market in India is witnessing a meteoric rise. Financial Express, February 6. https://www.financialexpress.com/brandwagon/how-the- wellness-market-in-india-is-witnessing-a-meteoric-rise/2189156/

- Baumgartner, H. , & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Consumer Marketing, 13, 139–161. 10.1016/0167-8116(95)00038-0 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Billore, S. , & Anisimova, T. (2021). Panic buying research: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45, 777–804.

-

- Chaudhuri, S. (2020, July 28). Lysol maker seeks to capitalize on Covid hygiene concerns in hotels, on planes. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/lysol-maker- seeks-to-capitalize-on-covid-hygiene-concerns-in-hotels-on-planes-11595939726

- Chopra, S. , Ranjan, P. , Singh, V. , Kumar, S. , Arora, M. , Hasan, M. S. , Kasiraj, R. , Kaur, D. , Vikram, N. K. , Malhotra, A. , Kumari, A. , Klanidhi, K. B. , & Baitha, U. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle-related behaviours—A cross-sectional audit of responses from nine hundred and ninety-five participants from India. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(6), 2021–2030. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.034 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Chriscaden, K. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on people’s livelihoods, their health and our food system. World Health Organization, October 13. https://www.who.int/news/item/13- 10-2020-impact-of-covid-19-on-people’s-livelihoods-their-health-and-our-food-systems

- Cohen, J. , Cohen, P. , West, S. G. , & Aiken, L. S. . (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioural sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar ]

- Das, D. (2018). Sustainable supply chain management in Indian organisations: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Production Research, 56(17), 5776–5794. 10.1080/00207543.2017.1421326 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Debroy, L. (2020, April 3). How online exercise sessions are keeping India fit during lockdown. Outlook. https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story /india-news-how-online- exercise-sessions-are-keeping-india-fit-during-the-lockdown/350026

- del Rio-Chanona, R. M. , Mealy, P. , Pichler, A. , Lafond, F. , & Farmer, J. D. (2020). Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: An industry and occupation perspective. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(Supplement_1), S94–S137. 10.1093/oxrep/graa033 [ DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Dsouza, S. (2020, March 30). Government expands lists of essential items to include hygiene products. Bloomberg. https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/government- expands-list-of-essential-items-to-include-hygiene-products

- Eroglu, S. A. , Machleit, K. A. , & Neybert, E. G. (2022). Crowding in the time of COVID: Effects on rapport and shopping satisfaction. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,

10.1111/ijcs.12669 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]64, 102760. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102760 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Fornell, C. , & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 8(3), 382–

388. [Google Scholar ]

- Galati, A. , Moavero, P. , & Crescimanno, M. (2019). Consumer awareness and acceptance of irradiated foods: The case of Italian consumers. British Food Journal, 121(6), 1398–1412. 10.1108/BFJ-05-2018-0336 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Garcı́a-Mayor, J. , Moreno-Llamas, A. , & De la Cruz-Sánchez, E. (2021). High educational attainment redresses the effect of occupational social class on health-related lifestyle: Findings from four Spanish national health surveys. Annals of Epidemiology, 58, 29–37. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.02.010 [DOI ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Gaskin, J. , & Lim, J. (2018). “Indirect effects”, AMOS Plugin. Gaskination’s StatWiki. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gordon-Wilson, S. (2021). Consumption practices during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 10.1111/ijcs.12701 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Guthrie, C. , Fosso-Wamba, S. , & Arnaud, J. B. (2021). Online consumer resilience during a pandemic: An exploratory study of e-commerce behavior before, during and after a

COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102570. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102570 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Hair, J. F., Jr. , Black, W. C. , Babin, B. J. , Anderson, R. E. , & Tatham, R. L. (2009). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar ]

- Hamilton, R. W. , Thompson, D. V. , Arens, Z. G. , Blanchard, S. J. , Häubl, G. , Kannan, P. K. , Khan, U. , Lehmann, D. R. , Meloy, M. G. , Roese, N. J. , & Thomas, M. (2014). Consumer substitution decisions: An integrative framework. Marketing Letters, 25(3), 305–317. 10.1007/s11002-014-9313-2 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Hampson, D. P. , & McGoldrick, P. J. (2013). A typology of adaptive shopping patterns in recession. Journal of Business Research, 66(7), 831–838. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.06.008 [ DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Hensher, M. (2020). Covid-19, unemployment, and health: Time for deeper solutions? The BMJ, 371, m3687. 10.1136/bmj.m3687 [DOI ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Hess, A. (2020, April 6). Our health is in danger: Wellness wants to fill the void. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/arts/virus-wellness-self-care.html

- Jacob, I. , Khanna, M. , & Yadav, N. (2014). Beyond poverty: A study of diffusion & adoption of feminine hygiene products among low income group women in Mumbai. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 148, 291–298. [Google Scholar ]

- Kansiime, M. K. , Tambo, J. A. , Mugambi, I. , Bundi, M. , Kara, A. , & Owuor, C. (2021). COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Development, 137, 105199. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Keane, M. , & Neal, T. (2021). Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Econometrics, 220(1), 86–105. 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.07.045 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Kennett-Hensel, P. A. , Sneath, J. Z. , & Lacey, R. (2012). Liminality and consumption in the aftermath of a natural disaster. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(1), 52–63. 10.1108/07363761211193046 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Khubchandani, J. , Kandiah, J. , & Saiki, D. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic, stress, and eating practices in the United States. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(4), 950–956. 10.3390/ejihpe10040067 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Kim, J. , Yang, K. , Min, J. , & White, B. (2021). Hope, fear, and consumer behavioral change amid COVID-19: Application of protection motivation theory. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 10.1111/ijcs.12700 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Kirk, C. P. , & Rifkin, L. S. (2020). I’ll trade you diamonds for toilet paper: Consumer reacting, coping and adapting behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research, 117, 124–131. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.028 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar ]

- Knowles, J. , Ettenson, R. , Lynch, P. , & Dollens, J. (2020, May 5). Growth opportunities for brands during covid-19 opportunities. MIT Sloan Management Review.

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/growth-op portunities-for-brands-during-the-covid- 19-crisis/ [Google Scholar ]

- Krause, D. R. , Pagell, M. , & Curkovic, S. (2001). Toward a measure of competitive priorities for purchasing. Journal of Operations Management, 19(4), 497–512. 10.1016/S0272-6963(01)00047-X [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Laato, S. , Islam, A. N. , Farooq, A. , & Dhir, A. (2020). Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102224. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102224 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Li, X. , Zhang, D. , Zhang, T. , Ji, Q. , & Lucey, B. (2021). Awareness, energy consumption and pro-environmental choices of Chinese households. Journal of Cleaner Production, 279, 123734. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123734 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Madnani, D. , Fernandes, S. , & Madnani, N. (2020). Analysing the impact of COVID-19 on over-the-top media platforms in India. International Journal of Pervasive Computing and Communications, 16(5), 457–475. 10.1108/IJPCC-07-2020-0083 [DOI ] [Google

Scholar ]

- Mahmud, M. , & Riley, E. (2021). Household response to an extreme shock: Evidence on the immediate impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on economic outcomes and well-being in rural Uganda. World Development, 140, 105318. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105318 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Mark, T. , Southam, C. , Bulla, J. , & Meza, S. (2016). Cross-category indulgence: Why do some premium brands grow during recession? Journal of Brand Management, 23(5), 114–

129. 10.1057/s41262-016-0004-6 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Martin, A. , Markhvida, M. , Hallegatte, S. , & Walsh, B. (2020). Socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 on household consumption and poverty. Economics of Disasters and Climate Change, 49(3), 453–479. 10.1007/s41885-020-00070-3 [DOI ] [PMC free articl[PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Master, F. (2020). Asia pivots toward plants for protein as coronavirus stirs meat safety fears. Reuters, April 22. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-asia- food/asia-pivots-toward-plants-for-protein-as-coronavirus-stirs-meat-safety -fears- idUKKCN224047?edition-redirect=uk

- Mathur, A. , Moschis, G. P. , & Lee, E. (2006). Life events and brand preference changes. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 3(2), 129–141. 10.1002/cb.128 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Mehrolia, S. , Alagarsamy, S. , & Solaikutty, V. M. (2021). Customers response to online food delivery services during COVID-19 outbreak using binary logistic regression. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(3), 396–408. 10.1111/ijcs.12630 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Milaković, I. K. (2021). Purchase experience during the COVID-19 pandemic and social cognitive theory: The relevance of consumer vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability for purchase satisfaction and repurchase. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(6), 1425–1442. 10.1111/ijcs.12672 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Minton, E. A. , & Cabano, F. G. (2021). Religiosity’s influence on stability-seeking consumption during times of great uncertainty: The case of the coronavirus pandemic. Marketing Letters, 32(2), 135–148. 10.1007/s11002-020-09548-2 [DOI ] [PMC free article[PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Mishra, P. , & Balsara, F. (2020). COVID-19 and emergence of a new consumer products landscape in India. Earnst and Young. https://assets.ey .com/content/dam/ey -sites/ey – com/en_in/topics/consumer-products-retail/2020/06/covid-19-and-emergence-of-new- consumer-products-landscape-in-india.pdf?download

- Montenovo, L. , Jiang, X. , Rojas, F. L. , Schmutte, I. M. , Simon, K. I. , Weinberg, B. A. , & Wing, C. (2020). Determinants of disparities in covid-19 job losses (No. w27132), National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar ]

- Mueller, R. O. , & Hancock, G. R. (2019). Structural equation modeling. In Hancock G. R., Stapleton L. M., & Mueller R. O. (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in social sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar ]

- Murthy, S. R. (2019). Measuring informal economy in India: Indian experience. In Seventh IMF Statistical Forum, Washington, DC.

https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Conferences/2019/7th-statistics-forum/session-ii-

murthy .ashx#:∼:text=In_terms_of_employment_share,indicating_the_level_of_outsourcing [Google Scholar ]

- Naeem, M. (2020). Understanding the customer psychology of impulse buying during COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for retailers. International Journal of Retail &

Distribution Management, 49(3), 377–393. 10.1108/IJRDM-08-2020-0317 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Nayal, P. , Pandey, N. , & Paul, J. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic and consumer-employee- organization wellbeing: A dynamic capability theory approach. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 10.1111/joca.12399 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Ojha, A. (2020, October 17). How COVID-19 changed fitness regime of Indians; here’s what a survey revealed. Financial Express. https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/health/how-covid-19-changed-fitness-regime- of-indians-heres-what-a-survey -revealed/2107825/

- Pakravan-Charvadeh, M. R. , Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, F. , Gholamrezai, S. , Vatanparast, H.

, Flora, C. , & Nabavi-Pelesaraei, A. (2021). The short-term effects of COVID-19 outbreak on dietary diversity and food security status of Iranian households (A case study in Tehran province). Journal of Cleaner Production, 281, 124537. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124537 [ DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Pantano, E. , Pizzi, G. , Scarpi, D. , & Dennis, C. (2020). Competing during a pandemic? Retailers’ ups and downs during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Business Research, 116, 209–213. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.036 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Paul, J. , & Bhukya, R. (2021). Forty-five years of International Journal of Consumer Studies: A bibliometric review and directions for future research. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(5), 937–963. 10.1111/ijcs.12727 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Pew Research . (2008, October 19). Family social activities and togetherness. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2008/10/19/family-social-activities-and- togetherness/ [Google Scholar ]

- Piyapromdee, S. , & Spittal, P. (2020). The income and consumption effects of covid-19 and the role of public policy. Fiscal Studies, 41(4), 805–827. 10.1111/1475-5890.12252 [ DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Podsakoff, P. M. , MacKenzie, S. B. , Lee, J. Y. , & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [DOI ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Prasad, A. , Strijnev, A. , & Zhang, Q. (2008). What can grocery basket data tell us about health consciousness? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 25(4), 301–309. 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2008.05.001 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Prentice, C. , Nguyen, M. , Nandy, P. , Winardi, M. A. , Chen, Y. , Le Monkhouse, L. , Sergio,

D. , & Stantic, B. (2021). Relevant, or irrelevant, external factors in panic buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102587. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102587 [DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PTI . (2020). COVID-19 pandemic leads to worries about job loss, anxiety on lack of social interactions: surveys. The Economic Times, September 29. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/covid-19-pandemic- leads-to-worries-about-job-loss-anxiety -on-lack-of-social-interactions- surveys/articleshow/78391128.cms?from=mdr

- Pullman, M. E. , Maloni, M. J. , & Carter, C. R. (2009). Food for thought: Social versus environmental sustainability practices and performance outcomes. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 45(4), 38–54. 10.1111/j.1745-493X.2009.03175.x [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Rakshit, A. (2020, May 10). Covid-19 impact: demand for personal hygiene, homecare products set to rise. Business Standard. https://www.business- standard.com/article/current-affairs/covid-19-impact-demand-for-personal-hygiene- homecare-products-set-to-rise-120051000431_1.html

- Rayburn, S. W. , McGeorge, A. , Anderson, S. , & Sierra, J. J. (2021). Crisis-induced behavior: From fear and frugality to the familiar. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 10.1111/ijcs.12698 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

-

Renner, B. , Baker, B. , Cook, J. , & Mellinger, J. (2020). The future of fresh: Patterns from the pandemic. Deloitte Insights, October 13. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry /retail-distribution/future-of-fresh- food-sales/pandemic-consumer-behavior-grocery-shop ping.html

Renner, B. , Baker, B. , Cook, J. , & Mellinger, J. (2020). The future of fresh: Patterns from the pandemic. Deloitte Insights, October 13. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry /retail-distribution/future-of-fresh- food-sales/pandemic-consumer-behavior-grocery-shop ping.html - Riise, T. , Moen, B. E. , & Nortvedt, M. W. (2003). Occupation, lifestyle factors and health- related quality of life: The Hordaland Health Study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 45(3), 324–332. 10.1097/01.jom.0000052965.43131.c3 [DOI ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Rogers, K. , & Cosgrove, A. (2020, April 16). Future consumer index: How Covid-19 is changing consumer behaviors. Ernst & Young. https://www.ey .com/en_gl/consumer-products-retail/how-covid-19-could-change-consumer-behavior

- Sánchez-Sánchez, E. , Ramı́rez-Vargas, G. , Avellaneda-López, Y. , Orellana-Pecino, J. I. , Garcı́a-Marı́n, E. , & Dı́az-Jimenez, J. (2020). Eating habits and physical activity of the Spanish population during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Nutrients, 12(9), 2826. 10.3390/nu12092826 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Sarmento, M. , Marques, S. , & Galan-Ladero, M. (2019). Consumption dynamics during recession and recovery: A learning journey. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 226–234. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.04.021 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

-

Singh, D. (2020). How is coronavirus impacting the streaming platforms with an increasing appetite of viewers? Financial Express, April 04. https://www.financialexpress.com/brandwagon/how-is-coronavirus-impacting-the- streaming-platforms-with-an-increasing-ap petite-of-viewers/1919916/

- Sneath, J. Z. , Lacey, R. , & Kennett-Hensel, P. A. (2009). Coping with a natural disaster: Losses, emotions, and impulsive and compulsive buying. Marketing Letters, 20(1), 45–60. 10.1007/s11002-008-9049-y [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

-

Sood, D. (2020). India has the potential to become a health and wellness hub. The Hindu Business Line, July 29. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/india-has-the- potential-to-become-a-health-and-wellness-hub/article32220274.ece

- Srinivasan, R. , Lilien, G. L. , & Rangaswamy, A. (2002). Technological opportunism and radical technology adoption: An application to E-Business. Journal of Marketing, 66, 47–60. 10.1509/jmkg.66.3.47.18508 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Suresh, S. , Ravichandran, S. , & P, G. (2011). Understanding wellness center loyalty through lifestyle analysis. Health Marketing Quarterly, 28(1), 16–37. 10.1080/07359683.2011.545307 [DOI ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Teisl, M. F. , Levy, A. S. , & Derby, B. M. (1999). The effects of education and information source on consumer awareness of diet–disease relationships. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 18(2), 197–207. 10.1177/074391569901800206 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- United Nations . (n.d.). Everyone included: Social impact of COVID-19. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/everyone-included-covid-19.html [Google Scholar ]

- Verikios, G. , Sullivan, M. , Stojanovski, P. , Giesecke, J. , & Woo, G. (2016). Assessing regional risks from pandemic influenza: A scenario analysis. The World Economy, 39(8), 1225–1255. 10.1111/twec.12296 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Wernau, J. , & Gasparro, A. (2020, October 5), People are eating healthier and cooking more, food execs say. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/consumers- are-eating-healthier-and-cooking-more-food-execs-say-11601926763

- Witteveen, D. (2020). Sociodemographic inequality in exposure to COVID-19-induced economic hardship in the United Kingdom. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 69, 100551. 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100551 [DOI ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar ]

- Yap, S. F. , Xu, Y. , & Tan, L. (2021). Coping with crisis: The paradox of technology and consumer vulnerability. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45, 1239–1257. 10.1111/ijcs.12724 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]

- Yeung, R. , & Yee, W. M. (2012). Food safety concern: Incorporating marketing strategies into consumer risk coping framework. British Food Journal, 114(1), 40–53. 10.1108/00070701211197356 [DOI ] [Google Scholar ]