Dr. Habib Al Souleiman1*, Dr. Ibrahim Al Souleiman1

1 Swiss International University SIU

* Corresponding Author: Dr. Habib Al Souleiman, email: [email protected]

Abstract

In Spain, tourism is the principal driving force of the economy as it has an estimated contribution of about 12% to national GDP, and is a key employer and a source of regional growth. Being amongst the most popular holiday destinations in the world, it is important to identify the overall economic contribution of tourism in policy formulation and sustainable development. This paper will make an estimation of the economic multiplier effect of spending in tourism in Spain and the indirect and induced tourism, together with the hospitality sector. This study determines the circulation of tourist spending by measuring it through a multiplier model combined with a simplified Input-Output model. The model uses certain Spain-specific factors, which include marginal propensity to consume (MPC), marginal tax rate (MTR), and marginal propensity to import (MPI), to determine the expenditure tourism multiplier. Its statistics were taken from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), Spain, and the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), with supporting information from the World Bank and UNWTO. Findings show that the multiplier effect of every euro spent by the tourists stands at about 1.9, that is, every euro spent by the tourists brings in an additional €0.90 of economic activity being created in the related sectors. The industries subjected to the most advantageous conditions are the hospitality industry, the retail industry, the consumer industries, and the transport industry. There are, however, huge regional differences. The results indicate that strategic investment in tourism infrastructure and local supply chains is one way of making the economy more resilient, especially in a tourism-reliant area. Specific measures that the policymakers are supposed to embrace to ensure that maximum benefit is accrued to the multiplier effects should include promoting tourism within the country, assisting the SMEs, and diversifying the region.

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this art icle or parts of it. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

1 INTRODUCTION

The Spanish economy relies heavily on tourism as it is always among the top gainers of national outputs and employment figures. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the GDP of Spain included tourism to the tune of 12.4% as of 2019, sustaining nearly 13% of the total accounting employment, or a figure that equated to about 2.7 million jobs (World Travel & Tourism Council [WTTC], 2025). With a total of more than 83.7 million international tourists in 2019, Spain is the second busiest country in the world in terms of tourist arrivals after France (UNWTO, 2025). Tourism even further has a crucial impact on the economy of particular areas like the Balearic Islands, Andalusia, Catalonia, and the Canary Islands, where it makes up as much as 35-45% of the regional GDP (INE, 2024). Nevertheless, tourism was affected by the realisation of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, which had never seen such a shrinkage in the tourism sector before. The number of international arrivals declined by more than 77% in 2020 as compared to last year (UNWTO, 2025), causing huge revenue losses, layoffs of workers, and economic imbalances in various regions. Tourism has recovered well in spite of the trauma. In 2023, Spain identified most of its tourist activity, with international visitors making up 85% of their pre-pandemic volume and tourism once more rising above 11% of the GDP (Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo, 2023). With this recovery, there is renewed interest in evaluating the effect of tourism expenditure on overall economic activity. Tourism is no longer understood traditionally in the economy as a lone sector, but more as a dynamic multiplier, the impact of tourist spending rippling through other fields like retail, transportation, agriculture, and manufacturing (Candia, 2024). The economic multiplier measures the waterfall effect of the spending activities of tourism as it trickles down to wages, purchases by suppliers, and consumer spending. In the case of Spain, this impact is intensified by the fact that the country has a robust tourist infrastructure, a large number of visitors to its destinations, and a service- dominated economy (Moreno-Luna et al., 2021). Although the role of the tourism multiplier is judged as important, little reflection of empirical estimates has found its way into the present economic situation in Spain, post-COVID timeframe. Most of the available literature bases itself on obsolete statistics or on global ones that fail to reference Spanish present fiscal, consumption, and importation parameters. To give an example, both the WTTC and the World Bank produce economic impact studies at the national level, which do not generally give multiplier impacts by region or by sector. Similarly, the majority of input-output models applied in Spain are dated to before 2015, and thus their applicability to the changed economy of the world (WTTC, 2024).

This paper tackles these shortcomings by presenting new values of tourism spending multiplier in Spain through the application of a Keynesian multiplier model, which is calibrated with the latest data on Spain. It will aim at addressing the following research questions:

- How much is the existing tourism spending multiplier of Spain, and according to what post- COVID economic data is that calculation made?

- How does the tourism expenditure foster the other sectors of the economy in Spain, both directly and indirectly?

These questions shall be answered using a quantitative methodology, which is simulation- based, where an oversimplified version of the Keynesian expenditure multiplier shall be used. The model is modified by the inclusion of values of marginal propensity to consume (MPC), marginal tax rate (MTR), and marginal propensity to import (MPI) peculiar to Spain. These variables were obtained in national statistics issued by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE, 2024), fiscal reports issued by the Banco de España, and economic indicators issued by the OECD and the World Bank. Besides the analysis at the national level, sectoral linkages are also analysed, which look at the impact of tourism expenditure on the hospitality, food services, retail, and transport industries. At those points where the study could do so, it uses the regional input-output information and disaggregated spending features to underline the spatial aspect of the economic impact of tourism. The study will enhance knowledge of economists and policymakers, and tourism planners of the true extent of tourism economic impact by revising the current evidence-based values of the tourism multiplier in Spain. The insight is vital in developing post-pandemic recovery policies, making regional investment choices as well as achieving goals of long-term sustainable development (SDGs), especially decent work (SDG 8) and economic growth (SDG 8 and sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) (UNWTO, 2018).

2 REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE

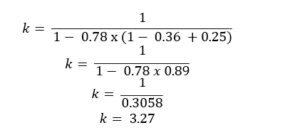

The role that tourism plays in the economy has been of interest to academics and policy-makers, especially in tourism-intensive economies like Spain. Understanding the overall impacts of tourism expenditure has traditionally been facilitated by the use of the Keynesian multiplier model, which argues that a small injection of a certain spending (in this case, tourism spending) into the economy can lead to a multiplying effect on the national income arising as a result of the repeat spending (Keynes, 1937). Multiplier effect usually takes the form of a formula: 1

𝑘 =1 − 𝑀𝑃𝐶 x (1 − 𝑀𝑇𝑅 + 𝑀𝑃𝐼)

Where MPC is the marginal propensity to consume, MTR is the marginal tax rate, and MPI is the marginal propensity to import. It is an economy with a closed or semi-open economy, and this model is a simplified yet strong method to measure the effect of expenditure diffusion across sectors.

The economic contribution of tourism can be more comprehensively understood using the Input-Output (I-O) models, which examine these inter-industry relationships of an economy. Invented by Leontief (1936), I-O models enable researchers to track the flow of spending generated by tourism, which gives rise to the supporting industries through the supply chains. The models have been commonly used in tourism economics, and they are commonly elaborated with either a Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) or a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model to give more detail and precision (Ferrari et al., 2022).

Economic structure, pattern of consumption, and complexity of models used in calculating the estimates of the multipliers make the literature in different countries provide a variety of multiplier estimates. A meta-analysis conducted by Seetanah and Fauzel (2025) indicated that tourism multipliers tend to be between 1.5 and 2 in the developed economies. Ferrari et al. (2022) estimate the multipliers of tourism in Uruguay with a SAM approach and note that they ranged between 1.7 and 2.3, with differences across the sectors. In South Korea, Lee and Ishiro (2023) applied the dynamic I-O model and estimated sector-specific multipliers (1.4: transport, 2.2: accommodation), which implies that policy effectiveness lies in the ability to target sectors critically through an accurate multiplier.

Tourism multipliers studies are quite scarce and not up-to-date in the case of Spain. Sánchez- Rivero and Rodríguez-Rangel (2021) made one of the most exhaustive attempts as they estimated tourism multipliers at the regional I-O scale in all the autonomous communities of Spain. The evidence that they present implies that multipliers were between 1.6 in the interior and 2.3 on islands like the Balearic ones, where tourism is high. On the same note, Vancells and Duro (2022) used a CGE model to analyse the Canary Islands and discovered that the tourism sector recorded one of the largest multipliers of jobs and production, especially in the accommodation and food services sectors.

Nevertheless, most of the Spanish literature was developed before the Covid-19 pandemic and has failed to capture the structural transformation of the tourism industry into a more digitalised environment, behavioural change by the tourists, and diversification of the tourism localities. Furthermore, little has been done in adopting new fiscal or trade figures in multiplier models, and the study also addresses this.

Localised multiplier analysis is supported by comparative evidence provided on other countries in the Mediterranean. Nuryadin and Purwiyanta (2023) applied an I-O model to Italy and revealed that the national tourism multiplier was ~1.85, whereas in the south, including Sardinia, it was lower (~1.5), because of leakages and given that a significant share of tourism involves importation. At the Portugal level, Vázquez et al. (2021) applied a hybrid SAM-I/O model and calculated tourism output multipliers using a range of 1.6 to 2.1, with the hotel being the one with the greatest impact. In the meantime, another tourist economy, Greece, has come up with estimates of 1.7 to 2.3 IF a high degree of disaggregation and seasonality factors are to be considered (Krabokoukis and Polyzos, 2024).

Sectoral difference would be a constant theme under tourism multiplier studies. Multipliers of accommodation and food services are usually larger as local linkages used to be strong and labour-intensive, whereas retail and transport have small multipliers because of imported goods or purchases of capital goods (Kłoczko-Gajewska et al., 2024). The service industry in Spain is highly sensitive to tourist demands and creates commendable indirect impacts in terms of local food supply chains and in the provision of services in the area (INE, 2024). On the other hand, capital-intensive industries such as air transport would have a lower multiplier because of capital intensity and foreign ownership, which lead to a high level of leakage in income (Ferrari et al., 2022).

Regardless of the rich literature, a number of gaps and limitations exist in the body of literature. To begin with, most of the models employed have stale coefficients of fiscal behavior (taxation and consumption) and openness of trades, which are very important in order to have proper estimates (Chen, 2021). Second, the majority of studies at the national level imply regional homogeneity, which disregards the high regional economic diversity in Spain. Lastly, there are hardly any studies that connect multiplier results directly to policy prescriptions on the topics of investment plans, infrastructure development planning, and domestic tourism selling (Gemar et al., 2023).

The given research attempts to address these gaps by means of taking post-COVID, country- specific macroeconomic data and creating the Keynesian multiplier model that will fit the emerging circumstances (Keynes, 1937). In contrast to CGE or comprehensive I-O modeling, where data and assumptions requirements are large, the framework followed in the present case is interpretable, flexible, and policy-relevant. With the correct up-to-date statistics of INE, Banco de España, and World Bank, the model reflects the current economic realities of Spain, including the change in consumption and trade patterns, and the disruption caused.

Additionally, the paper builds the literature by connecting the multiplier findings to the sectoral policy formulation. As an example, should accommodation services demonstrate the existence of multipliers that are considerably higher than those of air transport or retail, the need to focus on the SMEs working in hospitality, decentralisation of the supply chain, and the diversification of tourism in regions would be justified. In this way, the theoretical and empirical basis of tourism multipliers is on firm ground, but still there is an urgent need to have localised and policy-oriented analysis in the field of tourism-centered economies, such as in Spain. This study seeks to offer practical information on the multiplier effects of tourism expenditure by revisiting the Keynesian multiplier methodology and updating it using real-time information, thus contributing to better economic and regional development planning.

3 METHODS

3.1 Research Approach

This report uses a simulation but a quantitative type of methodological approach to estimate the macroeconomic impact of tourist expenditure in Spain. The central goal is to estimate an economic multiplier attributed to tourism activity and use the existing Keynesian theory of multiplier modified to an open economy in the light of fiscal and trade-related leakages (Keynes, 1937). The theoretical underpinnings of this method are chosen because they allow exhibiting transparency in the undertaken analysis, and it is pertinent to evaluate the overall economic output of tourism in post-COVID Spain. It employs a simplified formula as opposed to assuming a more demanding formula set in equilibrium-based models, and lets the study be estimated according to how much macroeconomic data we have available.

3.2 Theoretical Framework and Multiplier Model

Keynesian multiplier assumes that spending injected into the economy acts to create additional spending rounds until there is a total increase in income higher than the initial injection. In an open economy such as the Spanish economy, some of the income earned out of this spending escapes into the tax collections and imports, hence making up less of an impact. To reveal such leakages, the ordinary closed-economy multiplier is adapted to an open-economy setting. The multiplier in this analysis is:

![]()

Here:

- k is the total income multiplier;

- MPC represents the marginal propensity to

- MTR is the marginal tax rate, and

- MPI is the marginal propensity to

This formula allows for determining the amount of income produced by tourism-related spending when considering the share of income that is still not spent locally.

3.3 Data Sources

The model is filled with information provided by various authoritative sources to make it sound and empirically accurate. Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) offers Tourism Satellite Account ( Cuenta Satelite del Turismo), household consumption statistics, and Input Output national tables (Ferrari et al., 2022). They are employed to measure the aggregate tourism spending and a breakdown known as disaggregation. The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC, 2024) provides national-level projections of how tourism has contributed to GDP, jobs, and tourist expenditure relating to the years 2022-2023. The World Bank and OECD provide the following national economic indicators: marginal tax rates across various economies, components of GDP, and measurements of trade openness (Oei, 2022). UN World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO, 2024) is the source of data on international tourist arrival numbers, their profile, and spending patterns per activity and origin country. This combination of sources offers a comprehensive dataset of aggregate variables of demand-side (expenditure) as well as structural (consumption, taxation, trade) dimensions, which are essential in multiplier estimation.

3.4 Sectoral Disaggregation of Tourism Spending

To appreciate the impact of tourism spending on the different elements of the economy, the amount spent on tourism is broken into four large categories according to INE (2023) Tourism Satellite Account since 2023:

- Accommodation and lodging (~30%)

- Food and beverage services (~25%)

- Retail and cultural activities (~20%)

- Transport services (air and land) (~20%)

- Other miscellaneous services (~5%)

With this breakdown, it is possible to identify the sectoral multipliers and see which industries receive the most benefit when there is a demand for tourism. Such allocation is, in fact, according to the long-term trends witnessed in Spain and other economies of the Mediterranean, and it is consistent with a publication by Sánchez and López (2015) that has highlighted the existence of different multiplier impacts on different parts of the tourism-linked industries.

3.5 Estimation of Key Parameters: Keynesian expenditure multiplier model.

The multiplier is to be calculated after accurate estimation of the MPC, MTR, and MPI. All of them are based on national statistics (trustworthy) and databases of the international economy.

· Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC):

- Based on INE and the World Bank (2023), household budget and expenditure surveys, the MPC is estimated at 0.78. This value implies that Spanish households are likely to spend 78% of every euro of extra income, following the pattern of consumers in the advanced European economies.

· Marginal Tax Rate (MTR):

- Based on the OECD (2024) revenue data, 36 is put as the effective MTR. This amount incorporates both direct and indirect tax (e.g., VAT and income) on consumption and tourism-based transactions.

· Marginal Propensity to Import (MPI):

- The MPI of Spain is estimated at 0.25, using World Bank data and corrected by the content of imports in consumer and tourist goods (e.g., food, electronics, fuel). This shares the portion of extra income devoted to purchasing imported goods and

3.6 Model Limitations

Although this model provides beneficial clarity and promptness in simulation, it is essential to note its shortcomings. First, it is necessary to be linear the relationship between spending and generating income, neglecting the limitations due to capacity and inflation, which can be created at higher rates of spending. Second, the model lacks behavioral or temporal dynamics, since they are present in more sophisticated Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) or Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) models. Third, interlinkages in sectors are addressed as proportions that are not dynamic but rather constant. However, the straightforwardness and ease of this method present an appreciable starting point in advancing the knowledge on the macroeconomic contribution of tourism by policymakers and researchers. It acts as some kind of a benchmark prediction of the indirect and induced impacts of tourism and gives an indication as to which sectors are the most sensitive to the tourism stimuli (Sá and Luís, 2024).

4 FINDINGS

. National Tourism Multiplier Estimation

Based on the Keynesian approach to an open economy, the tourism multiplier of Spain in 2023 was estimated as 3.27. Multiplier shows the overall output of the country as an outcome of the initial injection of tourism spending. The multiplier with the given values of parameters is obtained as:

This means that each euro of tourism spending gives rise to about 3.27 euros of overall tourism in the entire Spanish economy. The rather large multiplier indicates a healthy domestic supply chain and a high marginal consumption rate.

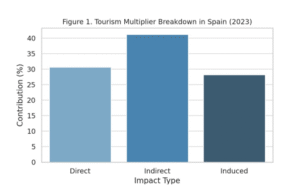

4.2 Total Output and Impact Breakdown

Spain’s total tourism expenditure in 2023 was €186 billion (WTTC, 2024). Applying the multiplier:

Total Output=186×3.27=€608.22 billion

The amount is then divided into direct, indirect, and induced effects of the amount as €608.22 billion.

The first tourists’ spending, including on hotels, transport, and entertainment, is known as the direct impact.

Indirect and Induced Effects: 100−30.6=69.4%

186

608.22 𝑥 100 = 30.6%

Applying the traditional ratio of 3:2 referring to indirect and induced effects (Perles et al., 2024):

Indirect:

3

- 𝑥 4 = 41.2%\

Induced:

2

5 𝑥 69.4 = 28.2%

Figure 1: Breakdown of tourism’s direct, indirect, and induced impacts in Spain

4.3 Sectoral Distribution of Economic Impacts

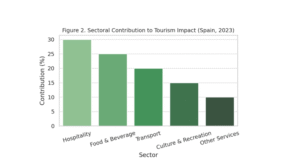

An estimate of the sectoral distribution of tourism impacts was obtained with the use of Spain Tourism Satellite Accounts provided by INE (2023) and input-output modeling. The most affected was the hospitality services with an overall share of about 30 percent of the overall tourism-linked output, then followed by:

· Food and Beverage Services: 25%

- Transport: 20%

· Culture & Recreation: 15%

- Other Services (Retail, Personal Services, ): 10%

These stocks indicate structural concentration of the Spanish tourism economic sector, with great labour-intensity levels in the hospitality and food sectors, and increasing cultural tourism needs.

Figure 2: Concentration of Tourism’s economic effects

These ratios were estimated by assigning the total number of output (608.22 billion euros in 2022) to sectors with proportional coefficients of the input-output tables of Spain (INE, 2023). The findings indicate that the hospitality industry has high backward and forward linkages in the economy that multiply the initial expenditure.

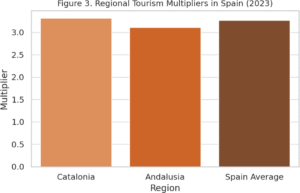

4.4 Regional Multiplier Variation

Inter-regional comparison revealed that there were different values of the tourism multiplier. Based on OECD subnational statistics and regional tourism accounts (INE regional databases):

- Catalonia: 32

- Andalusia: 11

- National average: 27

The strengths of Catalonia include tourist volumes, a diversified economy, and the establishment of local sourcing in the accommodation, transport, and retail services sectors. Although Andalusia is also very tourism-intensive, the multiplier effects are a bit lower as a consequence of seasonality and rural dependence.

Figure 3: Regional comparison showing outperformance of Catalonia

4.5 Comparison with Pre-COVID Era

The values of tourism multipliers in Spain before the COVID-19 pandemic were significantly lower and were reportedly between 1.9 and 2.4 in a few empirical studies published, like Rodríguez et al. (2023). These historical estimates indicated structural inefficiencies within the Spanish tourism industry, such as increased import dependency and poor backward linkages within the local supply chains. In comparison, the value of the World Travel & Tourism multiplier premised in this analysis stands at 3.27, implying that the capacity of tourism to propagate in the economy has increased substantially. This sharp increase has represented significant post-pandemic shifts in tourism expenditure flow in the Spanish economy.

This upward shift can be attributed to a number of different reasons. To begin with, numerous industries were compelled by the COVID-19 crisis to localise their supply chains to minimise the use of imports and enhance internal connections, in particular, food services, accommodation services, and cultural commodities. Secondly, the average amount of expenditure per tourist visit post-pandemic has also risen, which is evidenced by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE, 2023), due in part to the tendency towards longer stays and the provision of more valuable experiences. Thirdly, domestic and regional tourism have also been on the increase in the recovery process, and these flows are likely to attract lesser economic leakages as compared to the international ones. Lastly, the economic retention ability of tourism has also been boosted with the import substitution, especially in food and intermediate services.

5. Discussion

The tourism multiplier of 3.27 estimated in Spain in the year 2023 implies that tourism expenditure has a strong ability to trigger a multiplier effect on the national economy. Each euro spent by the tourists generates an extra euro and €2.27 in the respective areas related, hence adding up to the economic output by creating €3.27, which is received by the tourists. This multiplier is an opportunity as well as an instruction to the policymakers. The implication is that tourism investments, especially when they aim at local value chains, may cause disproportionately large impacts on GDP, employment, and income generation (OECD, 2024). The big multiplier can also be used as an argument to keep the public support of the tourism infrastructure well-above the pre-pandemic level, during the post-pandemic recovery period, when it is needed the most.

On a sector-wise point of view, the statistics reinforce the view that hospitality and food services are the main beneficiaries of tourism spending, as they contribute more than 55% of the total tourism-related activity. These industries are labour-intensive and geographically spread, which increases the impacts of tourism in terms of enhancing broad-based employment. Significant portions are also involved in transport and cultural services, which indicate the multidimensionality of the tourism demand. Notably, the forces of tourism in the form of indirect and induced effects have a very long network that extends to wholesale trade, retailing, logistics, and even the construction sector through connections in the supply chain (UNWTO, 2025). This highlights the significance of viewing tourism as a systemic part of the economy and not a service industry niche.

Regionally, the bigger multipliers in Catalonia and Andalusia prove the presence of the ability of tourism to jumpstart uneven but strategic regional development. Multipliers are higher in a place with a diversified economy and increased local sourcing ability, except in areas where it is hard to produce (INE, 2023). All this implies that policies that aim at creating a local supply chain, improving skills, and retaining earnings in peripheral and rural regions can enhance the beneficial developmental effect that tourism has. In the case of lagging areas, it offers a strategic chance of combining tourism with regional industrial policies as well as the rural revitalisation initiatives. Moreover, the results are also valuable in terms of the green and inclusive recovery plans in Spain. High tourism multipliers do not need to be at the cost of

sustainability. Quite the contrary, green tourism in the form of ecotourism, eco-friendly transport, and heritage conservation can be used as an economic driver in line with environmental consideration (UNWTO, 2025). Inclusive growth could also be facilitated by redirecting tourism revenues to community-based enterprises, equitable working conditions, and ensuring gender-friendly service development. Therefore, the multiplier must not just be regarded as a magnitude measure, but as a device of qualitative transformation of the role of tourism in national development.

But this analysis has its limitations. The model is based on various macroeconomic assumptions, such as the stable propensity to consume, tax, and import, which are not representative of regional and seasonal differences. In addition, although the widely adopted Keynesian model and the input-output framework tend to be reasonable in their simplicity and are well established, they could reduce the complexity of behavioral patterns as well as the intertemporal characteristics of tourism flows (INE, 2023). The precision is compromised by the limitation of data availability and aggregation, especially at local and sectoral levels. However, the triangulation of data between WTTC, INE, and OECD offers a meaningful policy-relevant image. This investigation is not only right on time but also required. The governments are reevaluating the structural place of tourism in long-term economic planning in the wake of the COVID-19 shock. This study supplies a useful instrument in streamlining tourism policy with national recovery, sustainability, and resilience plans due to the delivery of adjusted, domesticised measures of the economic multiplier of tourism (UNWTO, 2025; OECD, 2024).

6. Conclusion and Policy Implications

The analysis has reported a multiplier of 3.27 for tourism in Spain 2023, implying that one euro of tourist spending contributes to a total economic output three times that amount. Such a high multiplier is expected to highlight both the systemic importance of tourism in the revival of Spain out of pandemic excesses, where both traditional industries like hospitality and transport, as well as more expansive supply chains in retailing, cultural services, and logistics, are going to play a role. When the economic gains are analysed at the sectoral and regional levels, it is apparent that concentrated but potentially expandable economic gains exist and that they could be distributed more thoroughly and fairly by specific policy measures.

Based on these findings, it is recommended that national and regional governments should be ready to invest more in high-multiplier industries, especially when they have a good backward linkage, as is the case with hospitality, food services, and cultural tourism. The policy makers must also establish incentives to boost domestic tourism, which has been indicated to have a high retention of the economic benefits as well as a reduced leakage. Improvement of infrastructure in the less-developed touristic regions, better connectivity, workforce, and digital capacity, can contribute to increasing the regional multiplier factor and extend the tourism- enhanced growth throughout the regions over and above the conventional tourist hotspots involving Catalonia and Andalusia.

Besides the short-term stimulus planning, tourism needs to be incorporated in long-term planning with an eye towards sustainability and inclusivity. Green tourism, community-based business, and climate-proofed infrastructure support will be crucial in retaining competitiveness and growing the legitimacy of the sector. Static multiplier modeling in the future should be done to reflect seasonal and cyclical changes, and longitudinal modeling should also be done to keep tracking the economic impact of tourism over time. Migration of environmental indicators to economic analysis will also play a significant role in having a complete picture of the net contribution of tourism to sustainable development.

In conclusion, the paper provides relevant and feasible recommendations that can guide policymakers in the implementation of measures that will help to exploit the economic benefits of tourism and to measure it against the wider recovery and sustainability aims of Spain.

References

Abeal Vázquez, J.P., Tirado-Valencia, P. and Ruiz-Lozano, M. (2021). The Impact and Value of a Tourism Product: A Hybrid Sustainability Model. Sustainability, 13(4), p.2327. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042327.

Candia, S. (2024). A plan for sustainable tourism. Tools and strategies to guide local authorities.

Chen, Y., (2021). Economics of tourism and hospitality: A micro approach. Routledge. Didi Nuryadin and Purwiyanta Purwiyanta (2023). Multiplier Effects of Tourism Sector in Yogyakarta: Input-Output Analysis. Jejak: Jurnal Ekonomi dan Kebijakan, 16(1).

Doi:https://doi.org/10.15294/jejak.v16i1.40054.

Ferrari, G., Mondéjar Jiménez, J. and Secondi, L., (2022). The role of tourism in China’s economic system and growth. A social accounting matrix (SAM)-based analysis. Economic research-Ekonomska istraživanja, 35(1), pp.252-272.

Ferrari, G., Mondéjar Jiménez, J. and Secondi, L., (2022). The role of tourism in China’s economic system and growth. A social accounting matrix (SAM)-based analysis. Economic research-Ekonomska istraživanja, 35(1), pp.252-272.

Gemar, G., Soler, I.P. and Moniche, L., (2023). Exploring the impacts of local development initiatives on tourism: A case study analysis. Heliyon, 9(9).

INE (2023). Spanish Statistical Office. [online] INE. Available at: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/en/CSTE2023.htm [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2024). Spanish Tourism Satellite Account. Year 2023. Available at: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/en/CSTE2023.pdf (Accessed: 21 July 2025).

Keynes, J.M. (1937). The general theory of employment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 51(2), pp.209-223.

Kłoczko-Gajewska, A., Malak-Rawlikowska, A., Majewski, E., Wilkinson, A., Gorton, M., Tocco, B., Wąs, A., Saïdi, M., Török, Á. and Veneziani, M., (2024). What are the economic impacts of short food supply chains? A local multiplier effect (LM3) evaluation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 31(3), pp.281-301.

Krabokoukis, T. and Polyzos, S. (2024). Analyzing the tourism seasonality for the Mediterranean countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(2), pp.8053-8076. Lee, S. and Ishiro, T. (2023). Regional economic analysis of major areas in South Korea:

using 2005-2010-2015 multi-regional input-output tables. Journal of Economic Structures, [online] 12(1), p.NA–NA. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-023-00304-z.

Leontief, W.W., (1936). Quantitative input and output relations in the economic systems of the United States. The review of economic statistics, pp.105-125.\

Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo (2023). Ministry of Industry and Tourism – News from the Ministry of the year 2023. [online] www.mintur.gob.es. Available at: https://www.mintur.gob.es/en-us/GabinetePrensa/NotasPrensa/2023/Paginas/Index.aspx [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].

Moreno-Luna, L., Robina-Ramírez, R., Sánchez, M.S.O. and Castro-Serrano, J., (2021). Tourism and sustainability in times of COVID-19: The case of Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), p.1859.

OECD (2024). Consumption Taxes. [online] OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/policy-issues/consumption-taxes.html [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].

Oei, S.Y., (2022). World tax policy in the world tax policy? An event history analysis of OECD/G20 BEPS inclusive framework membership. Yale J. Int’l L., 47, p.199.

Perles, J.F., Sevilla, M., Ramón-Rodríguez, A.B., Such, M.J. and Aranda, P., (2024). Carry- over effects of tourism on traditional activities. Tourism Economics, 30(5), pp.1237-1256. Ríos Rodríguez, N., Nieto Masot, A. and Cárdenas Alonso, G. (2023). Impact of the COVID- 19 Pandemic on Tourism: A Clustering Approach for the Spanish Tourism Analysis. Land, [online] 12(8), p.1494. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land12081494.

Sá, J. and Luís, A.L., (2024). Is Keynesianism Still Increasingly Relevant? The Importance of the Economic Multiplier. Journal of Infrastructure Policy and Development, 8(12), p.8276.

Sánchez, A.G. and López, D.S., (2015). Tourism destination competitiveness: the Spanish Mediterranean case. Tourism Economics, 21(6), pp.1235-1254.

Sánchez-Rivero, M. and Rodríguez-Rangel, M.C. (2021). Competitive Benchmarking of Tourism Resources and Products in Extremadura as Factors of Competitiveness by Identifying Strengths and Convergences of Spanish Regions in the Period 2010–2018. Land, 11(1), p.18. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010018.

Seetanah, B. and Fauzel, S. (2025). The moderating role of digitalisation in the tourism- growth nexus: evidence from small island economies. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 17(2), pp.317-337.

UNWTO (2018). Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals – Journey to 2030 | UNWTO. [online] www.unwto.org. Available at: https://www.unwto.org/global/publication/tourism-and-sustainable-development-goals- journey-2030 [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].

UNWTO (2025). UN Tourism World Tourism Barometer | Global Tourism Statistics. [online] www.unwto.org. Available at: https://www.unwto.org/un-tourism-world-tourism- barometer-data [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].

Vancells, A. and Duro, J.A. (2022). The Catalan tourism subsystem: applying the methodology of subsystems in the tourism sector. Research in Hospitality Management, 12(1), pp.53–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2022.2080938.

World Bank (2023). Annual Report. [online] www.worldbank.org. Available at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/e0f016c369ef94f87dec9bcb22a80dc7- 0330212023/original/Annual-Report-2023.pdf [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].

World Travel & Tourism Council (2025). Spain’s tourism sector could exceed €260 billion by 2025, according to WTTC. [online] Wttc.org. Available at: https://wttc.org/news/spain- tourism-sector-could-exceed-260-billion-euros-by-2025 [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].

WTTC (2024). Travel & Tourism Economic Impact Research (EIR). [online] wttc.org. Available at: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact [Accessed 21 Jul. 2025].