Dr. Amina K. Rasheed¹, Prof. Jonathan T. Wexler¹, Dr. Sofia Martínez-León¹, Dr. Harunobu Saito², Dr. Amirul Reza Khan³,⁴

¹ Faculty of Business and Economics University of Nairobi, Kenya

² Centre for Sustainable Systems and Innovation, University of Leeds, United Kingdom

³ School of Business and International Affairs,Pontifical University of Chile, Santiago, Chile

⁴ Department of Political and Social Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Dr. Amina K. Rasheed Email: [email protected]

Abstract

A green market economy (GME) refers to an evolving global economic system that actively promotes sustainable development across economic, social, and environmental domains. This paper presents a theoretical model of the GME through the lens of cultural agency theory, framing it as an adaptive complex system. The progression of this economy is facilitated by a diverse range of institutional actors, including entities such as the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, and private commercial stakeholders, operating within dynamic and developing market environments that pursue sustainability-oriented goals. The modelling approach proposed herein comprises both a foundational axiomatic theory and a complementary, empirically verifiable supersystem theory. By constructing a green theoretical framework rooted in core propositions that define an adaptive substructure, this study further develops a corresponding superstructure intended for empirical validation. The research addresses gaps in achieving the sustainable development objectives outlined by UN-DESA, ultimately affirming the feasibility and relevance of establishing a green market economy.

Keywords:

Green market economy, Cultural agency theory, Adaptive complex systems, Sustainable development goals, Emerging markets, Institutional dynamics

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial–NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

1. Introduction

Crises tend to escalate in global contexts, particularly those relating to climate change, biodiversity loss, energy, food security, water availability, and more recently, financial and economic instability. In response, both governments and private sector actors are increasingly striving to shift toward a green economy, although the global economy continues to face challenges in recovering and sustaining growth. The green economy concept holds relevance across all economic systems, whether state-driven or market-oriented. According to the macroeconomic modelling outlined in the Green Economy Report (UNEP, 2011), investments in a green economy can enhance long-term economic performance and contribute to global wealth by expanding renewable resource stocks, minimizing environmental risks, and improving the capacity for future prosperity.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as adopted by the World Trade Organization (WTO), are targeted for achievement by 2030 and aim to foster equitable, predictable, and stable international trade relations (WTO, 2018). The Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN, 2018) emphasizes the imperative for all nations to implement this universal agenda to meet the SDG targets by the designated year.

The value of a green market-led economy (GME) can be interpreted through the framework of the 17 SDGs outlined by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA, 2015). These goals reflect an embedded cultural ethos and provide insight into the global economic framework that supports inclusive economic progress, societal development, and environmental sustainability. These goals can be categorized into three overarching dimensions:

(i) Economic:

This includes the eradication of poverty and hunger, as well as the promotion of sustainable employment (Goals 1, 2, and 8);

(ii) Social:

Encompassing individual well-being, inclusive education, gender equity, affordable and clean energy, sustainable infrastructure, reduced inequalities, resilient communities, and strong institutions fostering peace and partnerships (Goals 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 16, and 17)

(iii) Environmental:

Covering clean water access, responsible consumption and production, climate change mitigation, and the protection of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (Goals 6, 12, 13, 14, and 15).

Effective implementation of the GME concept necessitates coordinated action by global political leaders, civil society, and corporate stakeholders. This also requires policymakers and constituents to redefine traditional conceptions of wealth, prosperity, and human well-being. However, transitioning to a GME can be hindered by political inconsistencies, often resulting from administrative fragmentation—commonly referred to as the absence of “joined-up governance” (Klievink & Janssen, 2009).

China offers a pertinent example of these complexities. While the country has adopted a formal sustainable development framework since 2002, designed to address resource and environmental challenges through enhanced eco-efficiency (Geng & Doberstein, 2008), its policies remain contentious. The Chinese government often prioritizes technological advancement over addressing regional disparities related to industrial structure and energy use—factors that are crucial to long-term low-carbon economic strategies and sustainable development (Pan et al., 2019), which are vital to a robust GME.

Several critical concerns arise for GME adoption, particularly in emerging markets where the green economy framework remains underdeveloped. Previous resource governance reforms have faltered—such as in Indonesia—due to volatile markets and a disregard for political and economic realities (Castree, 2008; Swainson & Mahanty, 2018). Furthermore, current green economy models are often inadequate as they overlook the complexities associated with conflict resolution, trade-offs, and power asymmetries (Swainson & Mahanty, 2018). Financial constraints in the initial stages of green transitions also pose significant barriers, as key investors and major private sector actors often remain reluctant to commit resources (Swainson & Mahanty, 2018). According to the 2018 Green Economy Report (SDSN, 2018), no nation is currently on track to fully realize all SDGs, with environmental targets witnessing the least progress.

Addressing these challenges necessitates a GME capable of adapting to complex changes—critical to its long-term sustainability. This adaptability can be conceptualized through Cultural Agency Theory (CAT), which models the GME as an adaptive complex system, accounting for both internal dynamics and interactions with the external environment. In such a system, diverse governmental and commercial agents function within emerging market contexts, forming a basis for empirical exploration. As a culturally constructed phenomenon, the green economy is well-suited to be modeled through CAT and analyzed using principles from adaptive complex systems theory (Yolles, 2006). Hence, a resilient GME should be understood as a cultural entity, suitable for analysis using CAT (Yolles, 1999; 2006; 2018; U-tantada et al., 2019).

Within CAT, agency is conceived as an intelligent, autonomous, and self-organizing living system that recognizes its role within interactive environments. It possesses internal dynamics that influence its external market interactions. The theory is structured around three interconnected yet ontologically distinct systems that encapsulate socio-cultural dimensions, linked through process intelligences characterizing the living nature of the system. The substructure consists of foundational axioms that enable adaptive responses to complexity and the maintenance of viability. In contrast, the superstructure facilitates the construction of testable theoretical propositions. These systems collectively provide the capacity for self-regulation, communication, and cybernetic control (Yolles, 1999; 2006; 2018).

A GME model constructed through CAT serves as a diagnostic tool to evaluate the health of both the agency and its environment. This diagnostic capacity allows for the identification of substructural dysfunctions—such as deficits in adaptability or sustainability—within the GME or the interactive network in which it operates. These interactions are shaped by both internal agency attributes and external environmental conditions, including inter-agency behaviors. Internally, dynamic self-processes drive transformation and sustain viability. Diagnostic procedures within the superstructure are based on system outputs associated with specific substructural dynamics. This analytical framework offers practical solutions for strategic agents—such as the World Bank, WTO, and other stakeholders in emerging markets—working toward the SDGs. Therefore, this study aims to model and analyze the GME as a cultural agency using CAT, thereby addressing critical gaps in its alignment with UN-DESA objectives.

In light of literature addressing equity-based international entry strategies among emerging market multinationals, there is a growing need to empirically examine how such strategies impact performance and how they vary according to differing levels of institutional development (Surdu, Mellahi, & Glaister, 2018). A contextual diagnosis of the GME and its behavioral environment—along with the rapidly shifting dynamics of globalization—can offer deeper insights into complex transformations and strategic challenges. For the GME to foster resilience in both emerging markets and businesses, the development of an agency model becomes essential. Understanding how the green economy can generate favorable outcomes requires a comprehensive analysis of complex systemic interactions and the potential for transitioning toward innovative, sustainable business models (França et al., 2017).

This article presents a comprehensive examination of the GME through the application of CAT, focusing on the characteristics of emerging market environments. Drawing upon grounded theory, the study proposes a business model that facilitates awareness and understanding of how the GME and strategic superstructures within emerging markets can be integrated to further the advancement of sustainable development. The theoretical framework underlying our GME modelling approach is outlined across five key sections: (2.1) Cultural agency conceptualized as the green market economy; (2.2) GME as a market-oriented model; (2.3) the GME as a living system; (2.4) the role of strategic agency within GME’s emerging market context; and (2.5) the CAT-based model of the green market economy and its broader environment.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Cultural Agency Framed as a Green Market Economy

Amidst the dynamic evolution of economic, social, and environmental considerations and the increasing complexity of contemporary business contexts, the green market economy (GME) can effectively be conceptualized as a superstructural framework embedded within the substructural model of Cultural Agency Theory (CAT) (Yolles, 1999; 2006; 2018). CAT functions as a cybernetic paradigm for living systems that models complex adaptive systems with an emphasis on socio-cultural dimensions (Dominici & Yolles, 2016; Guo, Yolles & Di Fatta, 2017; Yolles & Di Fatta, 2017; Yolles, 1999; 2006; 2018). Within its substructure, CAT incorporates a metasystem governed by cybernetic principles, manifesting as an autonomous, culturally-informed “living” social system. Built upon this foundation, a superstructure emerges, defined through a series of testable propositions designed to address complex phenomena and allow for detailed situational analysis.

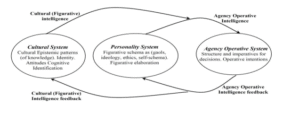

The theoretical basis of the superstructure in CAT draws from Bandura’s (2002) social cognitive theory, integrating attributes such as collective identity, cognition, affect, normative personality, shared purpose and intent, collective self-awareness, self-reflection, self-regulation, and self-organization. Agencies, within this framework, engage behaviorally with other agents and entities in their environment (Yolles, 2006). Furthermore, CAT enables diagnostic assessment of problems requiring resolution (see Figure 1). The metasystem within the substructure explains agency behavior in its context by incorporating a cultural system—housing attributes like knowledge and identity—a personality system, originally conceptualized to represent collective norms-based operations (Guo et al., 2016), and an operative system that translates strategic intent into behavior. These components are interlinked by process intelligences that characterize the agency’s living system properties, a concept elaborated further below.

Figure 1: CAT Substructural System Model (Yolles, 2016)

A cultural agency-based model of GME integrates comprehensive economic planning that encompasses investment and production activities. It involves institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO) to guide centralized green planning and ensure balanced market development, thereby sometimes curbing unregulated competition and monopolistic tendencies. The autonomous actions of individuals and enterprises aim to secure sustainable advantages, wherein traditional economic forces of supply—such as natural resources, labor, and capital—and demand—from consumers, businesses, and government—drive the production of sustainable goods and services. This model promotes the alignment of economic efficiency with sustainability, facilitating innovation, effective knowledge management, and long-term profitability for top-performing firms committed to environmentally responsible practices.

This strategic orientation fosters human well-being and social equity while reducing ecological risks and resource depletion. The GME framework, supported by policy-driven investment in transitioning toward a green economy, is aligned with the goals of inclusivity, resource efficiency, and low carbon development (UNEP, 2011). In essence, sustainable development is embedded in economic systems that study how resources are allocated under constraints to meet unlimited human demands (McTaggart, Findlay & Parkin, 1992), consistent with the agency model in CAT.

While the “green economy” concept does not supplant the broader notion of sustainable development, it is strongly interconnected with its thematic dimensions. These include: (1) environmental issues such as climate change, renewable energy, and the preservation of natural capital; (2) economic concerns including growth, competitiveness, and cost-effectiveness; and (3) social considerations, particularly governance structures that underpin green economic strategies. Practical implementation tools are employed to assess and monitor green economy initiatives (Loiseau et al., 2016), based on transparent legal frameworks that define property rights and regulate market interactions among citizens, businesses, governments, and civil society (CED, 2017). These structures facilitate rising wages, expanded trade benefits, greater consumer satisfaction, incentivized innovation, business lifecycle management, and competitive pricing mechanisms (Dorfman, 2016).

Accordingly, the empirical achievement of the SDGs necessitates incorporating the adaptable complexity of the GME within the CAT framework as it interacts with the broader emerging market environment.

2.2 Green Market Economy as a Strategic Market-Based Model

The GME can be utilized as a foundational model in market-based strategy aimed at optimizing returns through sustainable strategic management. Porter (1980, 1985) emphasized that market leadership—both in cost leadership and product differentiation—requires knowledge-based competition to secure resources via competitive advantage, thus yielding superior organizational performance (Porter, 1985). In this context, the GME encompasses core drivers of agency competitiveness, namely: customer bargaining power, supplier bargaining power, the threat of new entrants, the threat of substitute products, and overall industry rivalry. However, this external market orientation offers limited insight into an organization’s internal strategic capabilities.

Traditional strategic modeling falls short in adequately accounting for the intricate nature of competitive environments, particularly in establishing a lasting strategic edge. Research has shown that cooperative groups are often more resilient and adaptive than purely competitive ones (Nash, 1996). This gap can be addressed through alternative approaches like CAT. Brandenburger & Nalebuff (2002) expanded on Porter’s five forces model by introducing a sixth force—cooperation—thereby highlighting the strategic value of alliances within competitive markets (Porter, 1980, 1985). The six forces are defined as follows: (i) potential market entry, including challenges and entry barriers; (ii) threat of substitution, assessing the risks of product/service replacement and associated pricing dynamics; (iii) buyer power, considering buyer leverage and transaction volume; (iv) supplier power and potential competitive entry by new suppliers; and (v) intra-industry rivalry, assessing existing competitive intensity and characteristics (Guo et al., 2016).

In this agency-centered perspective, these six competitive forces become instrumental in evaluating the external environment and fostering sustainable strategic advantages. When green marketing is embedded across organizational activities—spanning product and service design, production processes, packaging, and promotional strategies—it ensures that societal, economic, and environmental interests are simultaneously protected. This integrated approach helps minimize ecological damage while promoting mutual benefit (Polonsky, 1994).

2.3 Conceptualizing the Green Market Economy as a Living System

Modeling the Green Market Economy (GME) as a living system enables its characterization as a self-aware, strategically oriented entity that engages in continual reflection, evaluation, and assessment. It is understood as an organic construct, comprising interrelated parts integral to a cohesive whole, and underpinned by process intelligence—critical for adaptability. This conceptualization draws upon third-order cybernetics and the principles of viable systems (Yolles, 2018). Consequently, the GME demonstrates an intrinsic interest in understanding and addressing its own dysfunctions or systemic pathologies.

Moreover, GME necessitates a collective cognitive framework to discern elements of cultural knowledge and to apply this knowledge discriminatively and effectively across diverse environments, thereby sustaining viable operational performance (Yolles, 1999; 2006; 2018).

Knowledge management emerges as a strategic asset in cultivating competitive advantage by integrating and leveraging core competencies. Its efficacy relies on the capacity of organizational leadership to foster a learning culture that encourages the generation, dissemination, and reapplication of knowledge—both individual and institutional—for business development and achievement of strategic objectives (Furlong, 2005; Yolles, 1999; 2006; 2018). Within the GME, knowledge management embodies a composite of values, transparency, ethical conduct, and trust, intimately connected to shifting political dynamics. These power relationships influence cultural agency and facilitate acceptance among stakeholders—individuals, coalitions, or institutions.

Knowledge processes—both intrinsic and extrinsic—shape the GME’s interactions with other organizational entities. These processes are enmeshed within cybernetic communication frameworks that create and transmit information. To ensure cohesive and viable operation in accordance with cybernetic principles, GME requires structured communication systems, wherein knowledge must be “knotted” effectively to prevent complications associated with knowledge transfer (Guo et al., 2016; Yolles, 2006). Knotted knowledge contributes positively to organizational reputation, facilitating customer trust, fostering innovation, and enhancing the dissemination of value-generating insights. This process is inherently linked to organizational learning (Calantone, Cavusgil, & Zhao, 2002), strategic innovation (Verona, 1999), and the capacity to sustain a competitive edge in highly dynamic environments (Tellis, Prabhu, & Chandy, 2009; U-tantada et al., 2019).

In addition to structured communication systems, all social communities—viewed as strategic alliances of individuals—must adopt collaborative approaches to develop coherent and effective communication mechanisms. Within the GME, the intersection of social collectives and political management is deeply political. Political management is essential to enabling individual and collective empowerment within social communities. These communities—ranging from national governments and economies to corporations and public/private institutions—operate within a web of political partnerships. These networks use power structures to shape institutional arrangements, manage information flows, and influence behavior through visible collaborative frameworks (Yolles, 2006; 2018).

Accordingly, GME necessitates a political management framework that enables each stakeholder to guide their sustainable development trajectory (Guo et al., 2016; Yolles, 2006). In today’s digital era characterized by networked societies and social learning, such a framework fosters leadership that prioritizes sustainability, improves operational behavior, and aligns personal, professional, and organizational goals. These frameworks also impact broader communities and organizational cultures (Mujtaba & Cavico, 2016; Mujtaba, Cavico, Senatip, & U-tantada, 2016). By pursuing sustainability and good governance, leaders within GME contexts may leverage power to exert influence or, alternatively, empower others in diverse, context-sensitive ways (Guo et al., 2016; Yolles, 2006).

Consequently, human capital within the GME must exhibit transformational and sustainability-oriented leadership styles grounded in the appropriate political culture. These leaders must be equipped with competencies in legal, ethical, moral, and operational domains—each vital to supporting intelligent, viable, and sustainable GME development as a dynamic living system integrated within emerging market environments.

2.3 The Green Market Economy as an Adaptive Socio-Economic System

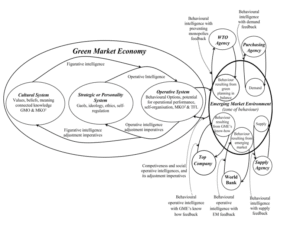

The current inquiry focuses on representing the GME as a living system characterized by its capacity for autonomous performance generation. Yolles (2016) has previously proposed a model wherein the market economy is ontologically delineated into three interdependent subsystems: a cultural marketing system, a strategic (regulative) business system, and an operative financial system (Figure 2). While the original model emphasized wealth creation, this refined version focuses on performance generation.

The GME, as a living entity, derives its adaptive capacity from operative and figurative intelligences, which sustain autonomy and facilitate systemic evolution. Performance generation mirrors wealth production in its autonomy and instrumentality. It materializes when strategic system trajectories—manifested as generic rule sets—are operationalized within the operative system, giving rise to specific transactional styles and structural mechanisms of performance delivery. These processes are ultimately informed and directed by the cultural marketing system.

Living systems are inherently purposeful and conscious, but can such attributes be ascribed to market economies? In social systems, purpose and consciousness are expressed through their human constituents. Consequently, these qualities cannot be directly attributed to emergent systems such as the GME, unless understood metaphorically or via the concept of collective consciousness. Similarly, attributing decision-making capabilities to the market economy requires acknowledgment of its constituent agencies. Therefore, the market economy should be regarded as an emergent agency formed through the complex interactions among organizational and strategic systems.

A living system may be defined as an adaptive activity system characterized by properties such as complexity, openness, self-organization, and the exchange of information and resources with its environment (Goldspink & Kay, 2003). Such a system comprises multiple social agents with adaptive capabilities and the capacity for influence (Bandura, 2001). The GME, conceptualized as a macro-level agency, is composed of micro-agents—individuals and collectives—whose interactions generate strategic behaviors.

This modeling framework facilitates the analysis of performance development within the context of global emerging market environments. It encompasses strategic agencies such as the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, supply and purchasing agencies, and major corporations. Understanding how these agencies interact provides insights into their contributions to global economic dynamics.

By applying a qualitative modeling approach grounded in Cultural Agency Theory (CAT), this representation of the GME enables exploration of its interactions within the emerging global market. Such modeling brings awareness to all participating entities, reinforcing their roles as integral components of sustainable, adaptive complex systems, as depicted in Figure 3.

2.4 Strategic Agencies Within the Emerging Market Context of the Green Market Economy (GME)

The global emerging market environment is not only intrinsically connected to the Green Market Economy (GME) but also to a range of market-oriented institutions such as the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and other relevant entities that align with the Cultural Agency Theory (CAT) model (see Figure 3).

• The World Bank

The World Bank aims to enhance the quality of life in developing nations by offering low- or zero-interest loans, policy guidance, and technical and knowledge-sharing assistance to low- and middle-income countries. These efforts target the generation of employment and opportunities for structural improvements in sectors such as education, healthcare, transportation, communications, agriculture, public administration, infrastructure, financial development, and the management of environmental and natural resources—thereby supporting economic, social, and environmental progress (Griffin, 2006; Ferrieres, 2017). In alignment with nations’ strategic industrial transformations, green growth policies promote green employment and environmental services, facilitated by active labor market interventions (Bowen, 2012).

• The World Trade Organization (WTO)

The WTO governs commercial and international trade rules, rooted in agreements negotiated and endorsed by the majority of the world’s trading nations and ratified by their respective parliaments. Its principal mission is to ensure that global trade operates in a smooth, predictable, and unrestricted manner. The WTO plays a pivotal role in promoting the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly through the establishment of equitable, stable, and transparent global trade relations that foster sustainable growth (WTO, 2018). Serving as a centralized authority for trade regulation, the WTO can impose temporary market constraints to mitigate monopolistic behavior, encourage competition, and enforce proprietary environmental and fiscal regulations. It does so through International Financial Institutions (IFIs) to ensure global policy acceptance (Konov, 2013). Fair competition not only stimulates innovation, productivity, and economic growth but also serves as a mechanism to alleviate poverty. This is especially vital in emerging markets, where equal competitive conditions contribute to lower prices, improved innovation, expanded consumer choices, better services, and enhanced access to information (Godfrey, 2008). The WTO, as an external catalyst, also plays a critical role in guiding business agencies—especially those in developing and developed economies—toward sustainable trajectories. External change agents are instrumental in overcoming entrenched organizational path dependencies (Hoppmann, Sakhel, & Richert, 2018).

• Emerging Market Agency

This agency supports developing economies experiencing accelerated industrialization and socio-economic growth. These nations are increasingly influential in global economic and political domains, often cultivating autonomous pathways for future development (Dominici & Yolles, 2016). By leveraging market expansion opportunities (Kohli & Jaworski, 1990), these agencies enable multilateral dialogue and dynamic negotiation processes (Dominici & Yolles, 2016).

• Purchasing Agency

Purchasing agencies are typically large-scale organizations, including government bodies and public-sector institutions. Their strategic influence extends beyond mere negotiation power. By fostering innovation and providing insights into factors influencing potential innovation outcomes, these agencies underscore the strategic significance of procurement (D’Antone & Santos, 2016). In emerging markets, purchasing behavior can shape market conditions through a wide array of internal and external actions. Rather than passively adjusting to existing offerings, these buyers actively influence market evolution via five key processes:

- Supply shaping — Influencing industry-wide supply strategies.

- Demand shaping — Interpreting competitor use of components as indicators of quality or risk.

- Need shaping — Articulating needs based on system specifications or existing solutions.

- Exchange object shaping — Refining product features and service characteristics in collaboration with sellers.

- Exchange mechanism shaping — Defining the nature of interactions and managing supplier relationships (Ulkuniemi, Araujo, & Tähtinen, 2015).

Supply Agency

These agencies manage their core and support operations sustainably to generate value not only for their own organization but also for society and the economy. Their sustainability approach encompasses environmental, ethical, social, and economic considerations in procuring goods, services, skills, and knowledge. Trust-based relationships between suppliers, clients, business alliances, and government-backed institutions are essential (Bennett & Robson, 1999). Research by Johnsen, Miemczyk, & Howard (2017) highlights how sustainable supply management and customer-supplier interactions are deeply embedded in networks shaped by stakeholder, institutional, and resource-based theoretical frameworks. Supplier selection is strategically crucial, particularly in the context of adopting green initiatives. Large enterprises face the challenge of identifying appropriate suppliers to implement sustainable practices and green their supply chains. The ability of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to innovate sustainably is increasingly being evaluated through structured supplier selection frameworks (Gupta & Barua, 2017). Institutional network relationships significantly influence GME’s ability to internationalize, offering access to, awareness of, and utilization of resources that either incentivize or constrain entrepreneurial activity in foreign markets (Oparaocha, 2015). Most collaborative engagements in technical and process innovation aim to expand business operations and profitability for all involved partners (Huggins, Johnston, & Thompson, 2012). Given this widespread influence, it is evident that purchasing agencies frequently partner with both large and small businesses to advance a wide range of environmentally responsible initiatives aligned with the achievement of SDGs.

Big Business (Big Business, 1905)

This term refers to economic entities composed of large profit-driven corporations, particularly regarding their influence on socio-political policies and their role in building robust economic frameworks and material wealth through established financial systems (Yolles, 2016). Such corporations are typically subjected to stricter regulations imposed by parent organizations and are often required to disclose more comprehensive environmental information compared to local enterprises (Ghazilla, Sakundarini, Abdul-Rashid, & Yusoff, 2015). According to Yaprak, Tasoluk, & Kocas (2015), organizational settings in both Eastern and Western emerging markets are evolving toward a more market-oriented structure.

These corporations often redefine competitive boundaries by transcending substitute industries through the seamless integration of multiple product categories into a unified device. They also explore complementary offerings by leveraging platforms embedded within their other products, fostering expansive ecosystems of developers (Giachetti, 2018). This evolution promotes facilitative leadership, advanced learning capabilities, innovation, and adaptability (Fey & Denison, 2003). In alignment with practices observed in developed nations (Baker & Sinkula, 1999), firms must enhance competencies in market-sensing, customer engagement, and channel-bonding to deliver exceptional customer value (Day, 1994). These skills are crucial for targeting brand-conscious middle-class consumers (Kravets & Sandikci, 2014) and implementing more market-responsive strategies (Khanna & Palepu, 2010).

To align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 (SDSN, 2018), organizations must cultivate green market orientation and general market orientation as culturally embedded strategic behaviors. This necessitates consistent effort across all functions and geographies to enhance customer satisfaction and brand loyalty. Entering international markets—especially those of developed nations with rigorous environmental standards (Ghazilla et al., 2015)—compels emerging markets (EMs) to recalibrate their operations within technologically advanced supply chains, consequently driving innovation potential (Lecerf, 2012).

Delivering green value in competitive environments also involves identifying small-scale partnerships with SMEs that can publicly elevate environmental performance (Schaper, 2002). Although SMEs frequently encounter limitations in finance, management, human resources, and internal expertise (Williams & Schaefer, 2013), as well as insufficient awareness regarding energy usage patterns (Gillingham & Palmer, 2014), collaboration with large corporations can mitigate these constraints. Such partnerships can help reduce environmental impact while also achieving financial efficiency (Richert, 2017). Moreover, they enable SMEs to capitalize on international opportunities and address challenges related to competition and global business operations (Bretherton & Chaston, 2005).

2.5 CAT Framework for Green Market Economy within Emerging Market Environments

The GME model presented in Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between the self-regulatory mechanisms of the Green Market Economy (GME) agency and the emerging market environment (EME), emphasizing the strategic opportunities to transition toward long-term sustainable performance across developed and developing economies.

This strategic model of the GME agency adopts a Cultural Agency Theory (CAT) framework composed of three interconnected systems: (1) a cultural system, (2) a normative personality system, and (3) an operative system. Each system features its own dynamically intelligent process networks—referred to as “Figurative Intelligence” (autogenesis or self-creation) and “Operative Intelligence” (autopoiesis or self-production)—which interlink these generic representations of GME.

“Figurative intelligence” serves as a learning-based attribute that formulates core interpretive explanations of reality through interactions with the external environment and associated knowledge systems (Yolles, 2006). This process employs feed-forward mechanisms to transform contextual attributes into actionable strategies, manifesting through the personality system to influence behavior. Conversely, “operative intelligence” functions as an instrumental attribute, forming a dynamic operative interface between the figurative and operative systems (Maturana & Varela, 1987; Schwarz, 1997), embedded with cultural significance.

Operational behaviors, implementation systems, regulatory codes, and internal norms are shaped within an environment populated by objects and practices defined by the agency itself—a depiction of how living (social) systems engage in self-production. Feedback mechanisms inform necessary adjustments during this process (Yolles, 2006).

These intelligent networks are cultivated through interdepartmental and interdisciplinary collaboration aimed at interpreting and contextualizing cultural attributes—such as values, norms, beliefs, and meanings—linked to knowledge systems. Key elements include green market orientation (GMO) and market orientation (MKO1), which are embedded in the cultural system and subsequently transmitted to the personality system for strategic implementation. These systems work together to establish a responsive agency capable of operating effectively within emerging market environments.

Figure 3: A conceptual model of the Green Market Economy in the context of the Emerging Market Environment

Both green market orientation (GMO) and market orientation (MKO1) are situated within the organizational culture framework, which comprises a complex set of values, norms, and symbolic systems that guide business operations (Barney, 1986). Within this cultural system, a shared foundation of assumptions, norms, and knowledge—including those related to GMO and MKO—coexists with goal patterns, ideological commitments, ethical standards, and regulatory frameworks that are part of the strategic system. The behavioral expressions of organizational functions, such as behavior-driven market orientation and transformational or sustainable leadership-based practices, reside in the operative system. These dimensions collectively offer insights into how organizational members internalize and develop these attributes in their professional environments, especially when responding to external challenges, thereby completing a cyclical model of organizational professional development.

Awareness of the influence that organizational culture exerts on management and staff is essential for understanding the mechanisms through which feedback is processed. Such awareness may help reduce the occurrence of moral disengagement behaviors within organizations (Petitta, Probst, & Barbaranelli, 2017). For instance, a technocratic safety culture—which is focused on results, competition, and innovation—contrasts starkly with a bureaucratic safety culture. The technocratic culture, while performance-oriented, may inadvertently lead to higher instances of moral disengagement, such as bypassing safety protocols, underreporting issues, or concealing errors (Petitta et al., 2017).

As a cultural attribute, GMO is grounded in green values and norms that must permeate both strategic and operational levels to support a holistic, eco-competitive advantage. This advantage unfolds through processes such as changes in product design, modifications in organizational culture, environmental impact assessments, and a final analysis of the competitive landscape (Moravcikova et al., 2017). GMO, as outlined by Papadas et al. (2017), comprises three main orientations. First is strategic green marketing orientation, which includes actions such as investing in renewable energy for product and service delivery, adopting low-carbon technologies, initiating R&D for environmentally friendly products, implementing partner selection criteria based on environmental policies, establishing dedicated environmental departments, participating in green business networks, engaging stakeholders in environmental discussions, and conducting market research to identify green consumer demands. Second is tactical green marketing orientation, which promotes environmentally conscious practices such as utilizing e-commerce, preferring digital over physical communication, adopting paperless policies, and using recyclable or reusable materials while absorbing the extra costs of offering environmentally responsible products or services. Third is internal green marketing orientation, which focuses on fostering an environmentally conscious internal culture through rewards, environmental considerations in hiring, internal competitions, committee formations for internal audits, employee education on green strategies, and the promotion of eco-friendly behavior and awareness among employees and consumers.

Meanwhile, MKO1 is rooted in the organization’s cultural orientation toward value creation for customers and is regarded as a deeply embedded institutional framework (Narver, Slater, & Tietje, 1998). It encompasses customer orientation, competitor orientation, and inter-functional coordination, all of which arise from organizational culture. These elements prioritize the generation of superior customer value as the central aim of all stakeholders, ultimately targeting organizational profitability (Narver & Slater, 1990). MKO1 supports a range of practices such as delivering superior customer value, demonstrating commitment to customer satisfaction, understanding consumer needs, integrating customer-centric strategies, facilitating interdepartmental resource sharing, aligning business functions with market strategies, disseminating internal and competitor-related information, identifying competitive opportunities, and promptly responding to market actions. These strategic and cultural elements are transferred into the normative or personality system, where they are internalized as cognitive attributes including attitudes, ideologies, goals, strategies, ethical codes, self-schemas, and self-image (Guo et al., 2016; Yolles, 2006), through a process identified as “figurative intelligence” that facilitates organizational responsiveness.

To continuously deliver timely and relevant products or services, especially within the domain of internal green practices and supplier management (Li, Ye, Sheu, & Yang, 2018), the operative system engages with these principles via the “operative intelligence” process. This ensures that the organization remains responsive to dynamic demands in its external environment over time. In this context, another interpretation of market orientation (MKO2) emerges as a behavioral expression within the operative system. MKO2 reflects actionable processes that enhance customer value, particularly in export markets or in response to environmental shifts and competitive pressures. Defined by Kohli, Jaworski, and Kumar (1993), MKO2 consists of three interrelated dimensions: the generation of market intelligence concerning current and future needs, the dissemination of this intelligence across the organization, and a corresponding responsiveness through innovation or adaptation.

To operationalize these dimensions, the GME must engage regularly with agencies in the emerging market environment to forecast future product or service requirements, conduct frequent market research, monitor evolving consumer preferences, and assess satisfaction. Additionally, it must identify significant changes in its competitive and regulatory environment, hold quarterly interdepartmental meetings to analyze market trends, and facilitate communication between marketing and other business functions. These efforts ensure timely awareness of significant developments among key stakeholders, thereby promoting coordination and shared responsibility across departments, which collectively enhance the organization’s value proposition within emerging markets.

Closely associated with other human resource capabilities in the operative system is transformational leadership, which is essential for fostering the green market and sustaining an interdependent economic model. This form of leadership plays a vital role in generating and preserving organizational value for both the agency and its stakeholders, helping align internal processes with broader SDG objectives for 2030. Transformational leadership (TFL), as characterized by Mujtaba, Cavico, Senatip, and U-tantada (2016), involves an understanding of legal, ethical, economic, social, and environmental expectations, combined with sustainable values that guide influence and behavioral change. TFL facilitates the achievement of organizational and personal goals by cultivating an environment conducive to long-term success. This leadership model also strengthens task-related team processes, such as reflexivity and team effectiveness, contributing to improved organizational productivity and performance (Lyubovnikova, Legood, & Mamakouka, 2017). It encompasses four core dimensions: self-awareness and global understanding, balanced information processing through inclusive decision-making, adherence to internalized moral standards, and relational transparency that promotes openness and authentic communication (Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, & Walumbwa, 2005). In promoting sustainability, transformational leadership supports ethical strategic business management by recognizing and advancing sustainable behaviors such as responsible resource use, ecological conservation, rights-based approaches, and broader environmental stewardship (Schuler, Rasche, Etzion, & Newton, 2017), which are essential for nurturing a global understanding of sustainability across all human resources within the GME framework.

The operative system functions as a structural element within the Green Market Economy (GME), serving as the source from which behavior emerges within a contextual environment populated by objects assigned with cultural significance. These objects reside within a broader framework—namely, the cultural system. Within this framework, organizational structure and operations are integrated to address concerns related to social structures, behavioral potential, operational performance, self-organization, and specific interactive functions. Execution-related information guides structural formation by outlining decision-making roles, associated operative tasks, and the procedural rules necessary to steer operative processes (Yolles, 2016; 2006).

In this context, the operative system of the green structure enables behavioral potential and decision-making authority, empowering specific operative behaviors within GME. It also incorporates cultural agency and communications linked to thematically meaningful constructs, referred to as the “life-world” (Schutz & Luckmann, 1974), in the dynamic environment of emerging markets. Operative intelligence feedback has the capacity to modify goals or adjust the methods through which these goals are pursued (Guo et al., 2016; Yolles, 2006). Concurrently, figurative intelligence feedback introduces the potential for changes in cultural knowledge or adaptations in the interpretation and application of contextual information.

The interrelations among operative activities and the competitive functionality of GME are crucial for sustaining the viability of dynamic agencies within complex systems. These interrelationships are inherently connected to GME’s behavioral intelligence, which encompasses the capability to comprehend and manage interpersonal dynamics and engage in adaptive social exchanges (Kihlstrom & Cantor, 2000). The degree to which GME performs these functions is measured through efficacy, which refers to the control mechanisms regulating emotional processes that influence how intelligences operate. This is achieved by acting on information flow between systems and adjusting the semantic processing functions of the intelligences (Guo et al., 2016; Yolles & Fink, 2011).

This systemic perspective offers promising implications for economies across the spectrum—whether developed or developing. A growing global awareness regarding environmental sustainability, fueled by multifaceted crises in climate, biodiversity, fuel, food, and water, has motivated the shift toward a green economy aimed at enhancing long-term global prosperity. Consequently, the realization of these shared opportunities across all nations is essential for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (SDSN, 2018).

3. Conclusion and Recommendation

This study presents a developed model of the Green Market Economy (GME), articulated through Cultural Agency Theory (CAT), which represents the global economic environment as an adaptive complex system. This framework is proposed to address existing gaps and facilitate problem-solving processes critical for the attainment of the SDGs.

Integrating sustainable development principles within economic systems enables the efficient allocation of limited resources to meet human needs and desires through the lens of agency as defined in CAT. This integration has the potential to significantly reduce environmental damage, climate-related risks, and adverse impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Such progress is achievable through active participation in systems that reinforce collective interests, particularly where green marketing orientation is embedded across diverse economic activities to safeguard societal, economic, and ecological dimensions.

Within this adaptive system, the emerging market environment includes active participation from global agencies such as the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and commercial agents (e.g., emerging market agencies, purchasing agencies, supply agencies, and top company agencies), collectively supporting sustainable development across economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

The proposed modeling framework comprises a general theory of the green market, rooted in a foundational substructural axiomatic theory, which is further extended into a testable supersystem theory. GME’s dynamic structure arises from the interplay of three generic systems within its interactive environment. Maintaining balanced relationships between GME and strategic agencies is critical for managing each dynamic component, mitigating pathologies such as ineffective management, suboptimal procedures, and inadequate communication that can disrupt the system’s structural and procedural flows.

By establishing a green theory based on a core set of axioms that define a living, adaptive substructure, this model affirms the validity of a functioning green market economy. Through the lens of complexity, this analysis offers a foundational understanding of how autonomous, responsive agencies—collectively embodied in GME—and their stakeholders interact to support green globalization in the decades ahead.

At the core of this model are the 17 SDGs, which call for coordinated action by both developed and developing nations. Heightened awareness and the formation of robust networks among strategic stakeholders—such as the World Bank, WTO, and various commercial agencies—are essential to strengthening green market resilience across all national contexts. Policymakers may leverage this theoretical model to better comprehend interdependencies within green administrative structures.

The insights generated herein may assist in the development of practical tools to secure a competitive advantage in green markets and provide clarity on how strategic agencies can align their policies for a smooth transition toward a green economy. This transition is vital to meet the SDGs by 2030 (U-tantada et al., 2019). Furthermore, the GME model is well-suited for navigating the complexities of conflicts, trade-offs, and power dynamics that accompany systemic transformation. Future research may build on this framework through reliable linkage analyses and empirical investigations (U-tantada et al., 2019), incorporating larger sample sizes and mixed-method approaches to test the external validity of the model’s qualitative propositions (Hesse-Biber, 2010).

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their sincere appreciation to the editor, reviewers, and Rajamangala University of Technology Phra Nakhon for their invaluable contributions.

References

Baker, W. E., & Sinkula, J. M. (1999). The synergistic effect of market orientation and learning orientation on organizational performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27, 411–427.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social Cognitive Theory: an agentic perspective, Annual Review of Psychology, 52:1–26

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied psychology, 51(2), 269-290.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–665.

Bennett, R. J., & Robson, P. J. (1999). The use of external business advice by SMEs in Britain. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 11(2), 155-180.

Big Business. (1905). Definition of big business by Merriam-Webster. Retrieved July 29, 2017 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/big%20business.

Bowen, A. (2012). Green growth, green jobs and labor markets. Policy Research Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5990

Brandenburger, A., & Nalebuff, B. (2002). Co-opetition: a revolutionary mindset that combines competition and cooperation in the marketplace; and the game theory strategy that’s changing the game of business. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc.

Bretherton, P., & Chaston, I. (2005). Resource dependency and SME strategy: an empirical study. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 12(2), 274-289.

Calantone, R. J., Cavusgil, S. T., & Zhao, Y. (2002). Learning orientation, firm innovation capability, and firm performance. Industrial marketing management, 31(6), 515-524.

Castree, N. (2008). Neoliberalising nature: The logics of deregulation and reregulation. Environment and planning A, 40(1), 131-152.

CED (Committee for Economic development) (2017). Regulation & the Economy. Retrieved 11 Nov, 2018 from https://www.ced.org/reports/regulation-and-the-economy

D’Antone, S., & Santos, J. B. (2016). When purchasing professional services supports innovation. Industrial Marketing Management, 58, 172-186.

Day, G. S. (1994). The capabilities of market driven organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58, 37–52.

Dominici, G., & Yolles, M. (2016). Decoding the xxi century’s marketing shift: an agency theory framework. Systems, 4(4): 1-13.

Dorfman J. (2016). Ten free market economic reasons to be thankful. Retrieved 11 Nov, 2018 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffreydorfman/2016/11/23/ten-free-market-economic-reasons-to-be- thankful/#5d231c8f6db7.

Ferrieres, M.d. (2017). Explaining the role of the World Bank, WTO and IMF in the global economy. Retrieved 20 February 2019 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 322886616_GLOBAL_ECONOMY_Explaining_the_role_of_the_World_Bank_WTO_and_IMF_in_t he_global_economy/citations

Fey, C. F., & Denison, D. R. (2003). Organizational culture and effectiveness: can American theory be applied in Russia? Organization Science, 14, 686–706.

Fink, G., & Yolles, M. (2011). Understanding organizational intelligences as constituting elements of normative personality. IACCM 2011, Ruse Bulgaria, 1-27.

França, C. L., Broman, G., Robèrt, K. H., Basile, G., & Trygg, L. (2017). An approach to business model innovation and design for strategic sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 155-166.

Furlong, J. (2005). New labor and teacher education: the end of an era. Oxford Review of Education, 31(1), 119-134.

Geng, Y., Doberstein, B. (2008). Developing the circular economy in China: challenges and opportunities for achieving ‘leapfrog development.’ International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 15, 231–239.

Ghazilla, R. A. R., Sakundarini, N., Taha, Z., Abdul-Rashid, S. H., & Yusoff, S. (2015). Design for environment and design for disassembly practices in Malaysia: a practitioner’s perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 331-342.

Giachetti, C. (2018). Explaining Apple’s iPhone success in the mobile phone industry: the creation of a new market space. In Smartphone Start-ups (pp. 9-48). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gillingham, K., & Palmer, K. (2014). Bridging the energy efficiency gap: policy insights from economic theory and empirical evidence. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 8(1), 18-38.

Godfrey, N. (2008). Why is competition important for growth and poverty reduction? Retrieved August 29, 2017 from http://www.oecd.org/investment/globalforum/40315399.pdf.

Goldspink, C., Kay, R. (2003), Organizations as self-organizing and sustaining systems: a complex and autopoietic systems perspective, International Journal of General Systems, 32 (5)459–474.

Griffin, P. (2006).The world bank. New Political Economy, 11(4), 571-581

Guo, K., Yolles, M., Fink, G., & Iles, P. (2016). The changing organization: agency theory in a cross- Cultural context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gupta, H., & Barua, M. K. (2017). Supplier selection among SMEs on the basis of their green innovation ability using BWM and fuzzy TOPSIS. Journal of Cleaner Production, 152, 242-258.

Hoppmann, J., Sakhel, A., & Richert, M. (2018). With a little help from a stranger: the impact of external change agents on corporate sustainability investments. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(7), 1052-1066.

Huggins, R., Johnston, A., & Thompson, P. (2012). Network capital, social capital and knowledge flow: how the nature of inter-organizational networks impacts on innovation. Industry and Innovation, 19(3), 203-232.

Johnsen, T. E., Miemczyk, J., & Howard, M. (2017). A systematic literature review of sustainable purchasing and supply research: theoretical perspectives and opportunities for IMP-based research. Industrial Marketing Management, 61, 130-143.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (2010). Winning in emerging markets: A roadmap for strategy and execution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Kihlstrom, J. F., & Cantor, N. (2000). Social intelligence. Handbook of intelligence, 2, 359-379.

Klievink, B., Janssen, M. (2009). Realizing joined-up government — dynamic capabilities and stage models for transformation. Government Information Quarterly, 26, 275–284.

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B.J. (1990). Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. The Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 1-18.

Kohli, A. K., Jaworski, B. J., & Kumar, A. (1993). MARKOR: A measure of market orientation. Journal of Marketing research, 30(4), 467-477.

Konov, J. I. (2013). Enhancing Markets (i.e. Economies) Transmissionability to Optimize Monetary Policies’ Effect. Retrieved August 29, 2017 from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/46950/.

Kravets, O., & Sandikci, O. (2014). Competently ordinary: new middle class consumers in the emerging markets. Journal of Marketing, 78, 125–140.

Lecerf, M. A. (2012). Internationalization and innovation: the effects of a strategy mix on the economic performance of French SMEs. International Business Research, 5(6), 2.

Y., Ye, F., Sheu, C., & Yang, Q. (2018). Linking green market orientation and performance: Antecedents and processes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 192, 924-931.

Loiseau, E., Saikku, L., Antikainen, R., Droste, N., Hansjürgens, B., Pitkänen, K., Leskinen, P., Kuikman, P., & Thomsen, M. (2016). Green economy and related concepts: an overview. Journal of cleaner production, 139, 361-371.

Lyubovnikova, J., Legood, A. T., & Mamakouka, A. (2017). How authentic leadership influences team performance: the mediating role of team reflexivity. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 59-70.

Maturana, H. R. & Varela, F. J., (1987). The Tree of Knowledge. London: Shambhala Publications.

McTaggart, D., Findlay, C., & Parkin, M., (1992). Economics in Action. Sydney: Addison-Wesley.

Moravcikova, D., Krizanova, A., Kliestikova, J., & Rypakova, M. (2017). Green marketing as the source of the competitive advantage of the business. Sustainability, 9, 1-13.

Mujtaba, B. G., & Cavico, F. J. (2016). Developing a legal, ethical, and socially responsible mindset for sustainable leadership. Florida: ILEAD Academy.

Mujtaba, B. G., Cavico, F. J., Senatip, T., & U-tantada, S. (2016). Sustainable operational management for effective leadership and efficiency in the modern global workplace. International Journal of Recent Advances in Organization Behavior and Decision Sciences, 2(1), 673-696.

Narver, J. C., & Slater, S. F. (1990). The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. The Journal of marketing, 54(4), 20-35.

Narver, J. C., Slater, S. F., & Tietje, B. (1998). Creating a market orientation. Journal of market- focused management, 2(3), 241-255.

Nash, J. (1996). Essays on Game Theory. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Oparaocha, G. O. (2015). SMEs and international entrepreneurship: an institutional network perspective. International Business Review, 24(5), 861-873.

Pan, W., Pan, W., Hu, C., Tu, H., Zhao, C., Yu, D., Xiong, J. & Zheng, G. (2019). Assessing the Green Economy in China: an improved framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 209, 680-691.

Papadas, K. K., Avlonitis, G. J., & Carrigan, M. (2017). Green marketing orientation: conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research, 80, 236-246.

Petitta, L., Probst, T. M., & Barbaranelli, C. (2017). Safety culture, moral disengagement, and accident underreporting. Journal of business ethics, 141(3), 489-504.

Polonsky, M. J. (1994). An introduction to green marketing. Electronic Green Journal, 1(2).

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: Free Press.

Richert, M. (2017). An energy management framework tailor-made for SMEs: case study of a German car company. Journal of Cleaner Production, 164, 221-229.

Schaper, M. (2002). Small firms and environmental management: predictors of green purchasing in Western Australian pharmacies. International Small Business Journal, 20(3), 235-251.

Schuler, D., Rasche, A., Etzion, D., & Newton, L. (2017). Guest Editors’ Introduction: corporate Sustainability Management and Environmental Ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(2), 213-237.

Schuler, D., Rasche, A., Etzion, D., & Newton, L. (2017). Guest editors’ introduction: corporate sustainability management and environmental ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(2), 213-237.

Schutz, A. and Luckmann, T. (1974). The Structures of the Life-world. London: Heinemann.

Schwarz, E. (1997). Towards a holistic cybernetics: From science through epistemology to being. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 4(1), 17-50.

SDSN (Sustainable Development Solutions Network). (2018). SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2018. Retrieved 11 Nov, 2018 from http://www.sdgindex.org/assets/files/2018/01%20SDGS%20GLOBAL%20EDITION%20WEB%20V9%20180718.pdf

Surdu, I., Mellahi, K., & Glaister, K. (2018). Emerging market multinationals’ international equity- based entry mode strategies: Review of theoretical foundations and future directions. International Marketing Review, 35(2), 342-359.

Swainson, L., & Mahanty, S. (2018). Green economy meets political economy: lessons from the “Aceh Green” initiative, Indonesia. Global Environmental Change, 53, 286-295.

Tellis, G. J., Prabhu, J. C., & Chandy, R. K. (2009). Radical innovation across nations: the preeminence of corporate culture. Journal of marketing, 73(1), 3-23.

Ulkuniemi, P., Araujo, L., & Tähtinen, J. (2015). Purchasing as market shaping: the case of component-based software engineering. Industrial Marketing Management, 44, 54-62.

UN-DESA (United Nations-Department of Economic and Social Affair). (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved 25, December, 2015 from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015.

UNEP (The United Nations Environment Programme) (2011). Towards a green economy: pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication. Retrieved 11 Nov, 2018 from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=126&menu=35

U-tantada, S., Mujtaba, B., Yolles, M., & Shoosanuk, A. (2016). Sufficiency economy and sustainability, Journal of Thai Interdisciplinary Research (extra issue: ISSN: 2465-3837), p. 84-94.

U-tantada, S., Yolles, M., Mujtaba, B. G., and Shoosanuk, A. (2019). Influential driving factors for corporate performance: A case for small and medium enterprises in Thailand. Kasem Bundit Journal, 20, 157-172. Retrieved February 30, 2019 from:

https://tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jkbu/article/view/173614/125136.

Verona, G. (1999). A resource-based view of product development. Academy of management review, 24(1), 132-142.

Williams, S., & Schaefer, A. (2013). Small and medium- sized enterprises and sustainability: managers’ values and engagement with environmental and climate change issues. Business Strategy and the Environment, 22(3), 173-186.

WTO (World Trade Organization). Retrieved 11 Nov, 2018 from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/coher_e/sdgs_e/sdgs_e.htm

Yaprak, A., Tasoluk, B., & Kocas, C. (2015). Market orientation, managerial perceptions, and corporate culture in an emerging market: evidence from Turkey. International Business Review, 24(3), 443-456.

Yolles, M. (1999). Management systems: a viable approach. London: Financial Times Pitman.

Yolles, M. (2006). Organizations as complex systems: an introduction to knowledge cybernetics (Vol. 2). Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age Publishing.

Yolles, M. (2016). Linking business and financial systems in the market economy: the case of China.

International Journal of Markets and Business Systems, 2(3)171-205.

Yolles, M. (2018). The complexity continuum, part 2: modelling harmony, Kybernetes, https://doi.org/10.1108/K-06-2018-0338.

Yolles, M., & Di Fatta, D. (2017). Antecedents of cultural agency theory: in the footsteps of Schwarz living systems. Kybernetes, 46(2), 210-222.

Yolles, M., & Fink, G. (2011). Agencies, normative personalities and the viable systems model. Journal of Organizational Transformation & Social Change, 8(1), 83-116.